"We Have To Think About What Progress Is"

Ponto Atelier is a young office from Portugal with works varying in places, programs and scales. They are based in Madeira Island, in the Atlantic Ocean and they are about to become much more visible soon, with several ongoing projects to be completed and their participation at “Fertile Futures” Exhibition, the Official Portuguese Representation of the Venice Architecture Biennale 2023, curated by Andreia Garcia. Şebnem Şoher talked to Ana Pedro Ferreira and Pedro Maria Ribeiro, founders of Ponto Atelier about their inspirations, being on an island and what it means to be sustainable today.

Şebnem Şoher: Hello, it is very nice to meet you. I would like to start with an introduction of you, by you. Can you please tell our readers about the studio’s background? Who are you, who is Ponto Atelier but perhaps more importantly how did you come together as a studio?

Ana Pedro Ferreira: Hello, we are Ponto Atelier; I am Ana Pedro, nice to meet you.

I am originally from Funchal (Capital of Portugal's Autonomous Region of Madeira), Madeira Island and Pedro is from Évora, Alentejo. We met when I went to Évora University to study architecture.

Pedro Maria Ribeiro: And I'm Pedro.

We started our academic journey together in Évora, and then Milan for a year and we can assume that the beginning of our studio was during that academic period. Because we started working there as a team and since then even when we started working with different studios we worked together. We were like a pack. The three years we spent at the Ventura Trindad Architecture in Lisbon was a very important period for us, because we started to coordinate the studio there and we decided that maybe we could try doing that for ourselves. During that period, we were working on some competitions by ourselves and there was a moment that we won the “Duas casas nas Ilhas Selvagens (Two houses for Savage Islands)” Competition.

APF: This was a very interesting competition about these deserted islands, nobody lives there and our proposal won. Then we had to give ourselves a name and so it became official. “Ponto'' means “dot” in Portuguese; dot has its meaning holistically. It can represent in a small way, so much. Inspired by Carl Sagan's “Pale Blue Dot”, that small dot represents the world. And in this sense, this competition officially launched the atelier as the southernmost point of Portugal. It made sense at the time...

Ponto is a continuation of that academic path. We didn’t really think there was a gap, a difference between the academic years and the “real world”, between the studio or professional life. Of course we have financial issues and also dealing with bureaucracy, and clients. But from an intellectual point of view, our way of investigation is a continuity.

PMR: We never looked at our projects as “Now we have a client” but still as “How to build an idea that is based on the research”. I think this is a method that starts at the University in a natural way. When we finished our studies, we were invited to teach at Évora University and then to do several workshops abroad. We continued this method and at the end it was a natural pathway which led us to the Ponto Atelier, to this point where we are today.

ŞŞ: Then maybe I can continue from this point. What is your design process like? How do you approach it when a design problem comes to you?

APF: We see every project, small, big or micro-scale as an opportunity to study something new. It is a chance to develop an idea and every single project is unique. We need to tell a different story each time. That’s why, in my opinion, each one of them has a different kind of graphic system.

We like to draw by hand, we love to do models and also collages, whatever we might need so that we can tell that story. Sometimes we take a process from one project and attach it to another. It is a big mix and not a fixed rule.

PMR: Yes, we don’t have a rule. I think the main idea is our vision for that specific place. It is a mixture of the concerns that this place gives us and ideas and references we have from other places. It depends on the project but we arrive at a tool that is efficient for communicating this idea.

APF: I think it’s important to say that the clients who come to us already know our work but we never give them what they think they need or what they ask us to do in the beginning. Usually the first thing we say is “Maybe it’s not going to be what you think it’s going to be. It will be more than what you expect”. This has been also the feedback from our clients, that the result has been more than what they thought in the beginning and that is very important to us. Because we don’t only respond to the problem they bring us. Neither in public competitions nor in the case of a private commission. We are trying to give more to that situation.

PMR: We are more interested in adding something to the idea of just building a certain something in a certain place.

ŞŞ: Can you maybe explain through concrete examples? This is very abstract right now. We could mention some projects. For example, the temporary installation you made in Azores. I wanted to ask about it very much. It is a very beautiful installation and also famous. Maybe that would be a good example for you to tell us a bit more about your process.

APF: Thank you. INBETWEEN pavilion is very dear to us. It was our first public building and it was temporary, so it doesn’t exist anymore and this aspect of it is also very beautiful.

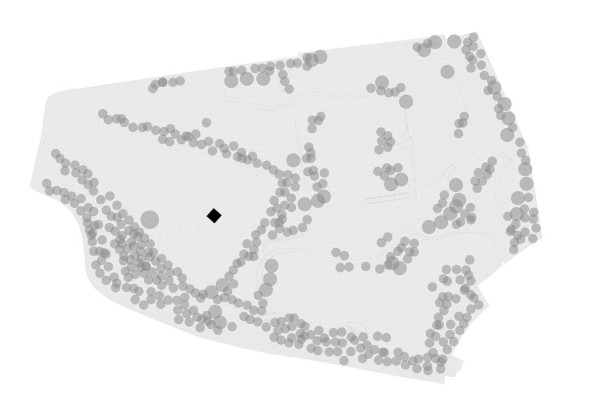

PMR: We were invited from Walk&Talk festival to do a small artistic residency in Azores, that was the beginning of it all, and was very important because we were interested in local materiality, topography, geography, local references giving shape to a place...

When we returned, we brought some small volcanic stones with us that are very specific from the Azores Islands. We put these stones in the studio for one year and it was after one year, in 2020, when they asked us to build something with a very small budget.

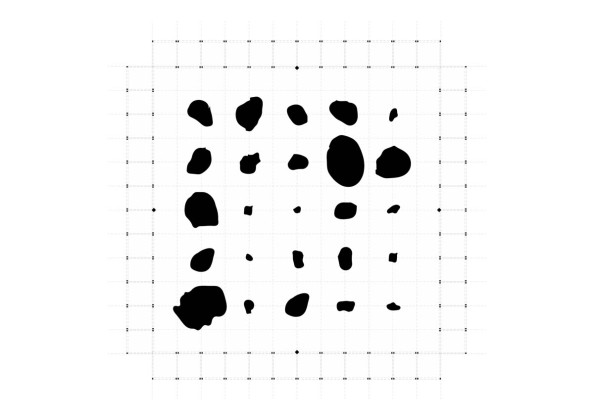

APF: This whole project was for the art festival context. When they commissioned, they didn’t give us a place, nor a program or a client. We just had a very low budget. So we started the project from the material of the place. There were two materialities, one permanent and one ephemeral. The ephemeral was the cryptomeria wood, very common in the Azores. It is originally from Japan but became endemic. On the opposite side was the permanent materiality of the installation, the volcanic stones.

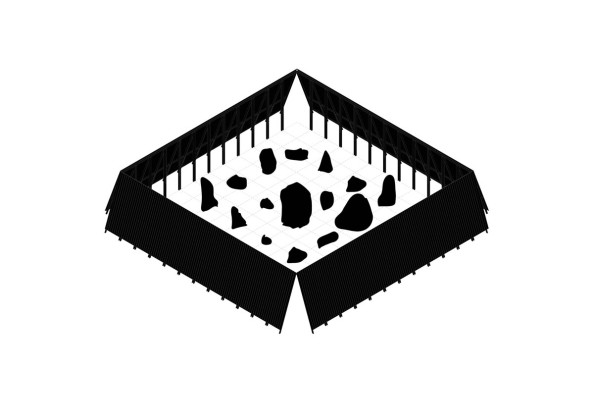

PMR: This was after the pandemic; everyone was closed at home. Therefore, the space we wanted and needed to be a collective space where we could be together. So we created a room without a ceiling, without a roof, without doors to be closed.

APF: It was a reflection of our time. During the pandemic we could go out but couldn't be together with other people in the same room. We wanted to create a space where we could be together.

PMR: We designed this square space where we had the stones placed in a very orthogonal 2 x 2 m grid which symbolises the distance between the bodies, in a kind of a sterile garden. We could be inside/outside together around the volcanic stones. The envelope was the cryptomeria wood, burned outside, which gave the black texture. It was a way of using fire as a material for construction. At the end, all of it was a volcanic system.

APF: We thought about the birth and the death of this project from the beginning, because we knew that it would be brought down some day at some point. It was very interesting though, after 6 months or so in a storm, the wooden part just disappeared. Then there were just the stones, which will remain and be part of that landscape. All this process was very poetic.

ŞŞ: Can we then talk about temporality? In general, it is very hard in architecture to acknowledge that the building might change, might disappear. I am curious about how you think about this topic. Do you think about time in your other projects as well?

PMR: We like to think about the projects at a certain point as a ruin, like a contemporary ruin. That means building our projects as the body structure that would provide a value of space that remains even if the construction might stop at one point. If the construction process is not finished, it has to survive and has a value of space. Normally buildings have a certain time but during their existence they need to be able to receive some changes. It can be the program but also just the finishes. For example, we try not to use plastic material, because we think that buildings have to get old in a healthy way, like a stone…

APF: Or like people. Aging has its own natural beauty. You have to think about the project now and the project in the future. Maybe now you can take a picture and it’s beautiful but you have to think about it in twenty years. The future is long, it exceeds us.

PMR: Architecture is of course related to life and the “now” is always changing. Something that stays longer than us has to respond to not only this now but to others.

ŞŞ: It is also a very relevant topic, right? I mean adaptive reuse.

APF: When you think about sustainability, I think that should be the main point.

PMR: Sustainability is more than gadgets and machines, all these completely glass buildings with ventilation systems and so on. We have to learn from the past. Now that we saw once more with COVID, our way of living constantly changes. Today we have a lot of information. We are living on Madeira Island in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, we can talk to you online, we have information from Japan. We have to learn a lot and there are no excuses now in globalisation. Of course we can try to do projects in architecture like in high fashion, meaning very specific projects for a very specific client. But architecture needs to deal with this specific idea of life and time, so we need to respond to the client and they should be very very proud of the project but it has to relate to the rest of the world.

In Portugal we have convents for example. In time they were used as military infrastructures and then as schools. Now they are most likely hotels. Churches become museums. We have a client who bought a small convent and wants to make a house there. It was a house for twenty people, now we will see.

ŞŞ: Since you mentioned a future project, what are your other upcoming projects?

APF: We are in a phase where we have different projects, in different phases, scales and places... Some housing projects in different sites of Madeira Island, some of them under construction. A farm in Alentejo. We won a competition for an urban design of a street in Merano, Italy, and soon we will have to start the project. Then we have more artistic projects such as scenography, and preparing our intervention for Venice Biennale´23.

PMR: It is really interesting to have all these different projects also because each of them are contaminated by each other, influence each other. We develop this scenography with shadows and the shadows appear in a small housing project where we build a garden pavilion that will have this system of shadows. For us it is an opportunity to do research in the studio and then they all affect each other.

ŞŞ: May I ask you about your relation to existing architectural knowledge? You mentioned geography, the brief from the client or the specific context. But are these the only influences? Do you have any architectural references? Do you see yourself as a continuation of any school, any canon, Portuguese or international?

PMR: We see ourselves somewhere between Critical Regionalist architecture and the contemporary international inputs which we receive from a wide geography. We like to follow interesting architecture from Belgium, Switzerland, etc… and at the same time also interested in looking at the history and local traditions.

APF: Yes, we try to look to the past, to the history of places and materials and ways of doing it. And in parallel also look for references worldwide. When we talk about regionalism and vernacular architecture kind of approach, there are elements added by the English or African influence, they adapted to climate and other conditions and in time became vernacular. In this sense we are trying to continue this history…

ŞŞ: Can we talk about being in Madeira? You already said that Évora is peripheral and then you chose to go even further from the centre. How is it not being at the centre, how does it work?

PMR: We came to Madeira in 2016. After a long period and experience in Évora and then some years in Lisbon. After those years, we were invited to be part of a team, which was convoked by the governance after some fire incidents here on the island. The team was formed by different architects. It was supposed to be four months, then one year, and then we started to have some work here.

APF: At that point we decided to stay and give it a try here. We had all these projects and the island itself has great potential. It has a great topography which for an architect is a big challenge, which makes it very interesting in the end.

PMR: There is a very special climate here. It’s very tropical and the weather has lots of influence from Africa. We noticed that doing architecture here has a lot of opportunity to develop spaces in a different way because of the weather. It was an opportunity to do research about different subjects. Also being in this ultra-peripheral territory had its advantages. We can have some distance to do our research but also we are living in the global world and we have a lot of connections. We can easily connect to other parts of the planet. What matters is, the different perspective and different way of working being in the middle of the Atlantic gives us. We ended up making new connections with other teams, for example from Italy. The close environment we work in might be more closed but the perspective becomes more open.

APF: We always have this hunger, the excitement to see other things happening in other places. We are physically working from the island but looking from outside the island. Our main concern might be the architecture in Madeira but we feel this obligation to look at what is happening around us. It is a good balance. To have a good base and to have the challenge of not staying enclosed in a peripheral system and absorb every information we can reach.

ŞŞ: I see that this is also related to our contemporary lifestyles. Maybe it would be different 20 years ago. Today what you do on a small scale can find responses from all around the world, maybe from someone who has similar concerns somewhere else. Do you have such experiences?

PMR: For other architects who look through our work, we believe that it might look like an exotic space. For example, we participated in a conference in Munich in January. It was a snowy day there and when we presented some projects from Madeira with all the sun and the banana trees, it was indeed very exotic to the students in Munich. In such contrast, we also rethink our own context.

APF: Madeira island is a paradise, and has enormous potential. But working here in architecture we know that it can be very challenging and is completely different from visiting and seeing from a very short time perspective.

We have in the island very good examples of modern architecture, which defines the best of architecture elements and ways of construction, and other few architects that are doing a great job and set a good example of resistance… But besides that and in a very general point of view there is a lack of architectural culture and to communicate some values.

ŞŞ: It becomes more important and also more visible to work in such exotic scenes, where one can feel the presence of nature and natural material, the more the climate change discussions become prominent. But Madeira also has a densely built environment, Funchal is very urbanised. How is it for you working in different contexts within the island?

PMR: In the context of Funchal specifically, the issue of construction and the issue of architecture are very different from each other.

APF: That is what we were saying before. There is a lot of construction but less architecture. Here architecture culture is missing. Imported construction systems are more common.

PMR: This is related to the idea of progress. If in the professions, in architecture, in engineering and administration we don’t discuss, people want a certain kind of visuality that is equal to progress for them. But that is a fast and visual response and it might create very big problems in the future. There is the way of thinking as if what is from outside is new and good. But we actually have a lot of material from the island that is sustainable. We have to think about what progress is.

ŞŞ: Sometimes we have the tendency to limit sustainability in architecture to materials. When I was structuring the questionnaire, I was perhaps also expecting to hear back some stories about if the nature of Madeira influences your choices of material. But what I heard was different. You told me about time and about systems in terms of sustainability.

PMR: I think it’s more interesting for us, when we think about the materiality, the value of time and the durability, which material can pass years in the best possible shape. For example, I personally don’t know any plastic material that is still nice after 5 years, but wood is. Concrete has a large ecological footprint, but if it has quality, is durable. And time is a way of sustainability.

APF: It also depends on where you are. In one place cutting woods can be terrible or if you have to bring the wood from the other side of the planet we cannot talk about sustainability.

PMR: But in Madeira for example, if you don’t cut some of the trees in the higher parts of the mountains there is a risk of fire. If you have to cut some tree, it is already material to be used for construction. It is more about the system than it is about a specific material.

ŞŞ: Thank you very much for your time. I am looking forward to seeing more about this topic in the Fertile Futures Exhibition at the Venice Architecture Biennale.

APF: Thank you very much, and see you at Biennale!

Related Content:

-

Let's Pastrami

-

Quake Museum

-

TM8

-

House 1 Porto

-

Open Call for Pavilion of Turkey, 18th International Architecture Exhibition of la Biennale di Venezia

-

Stories of Adaptation

-

Rural Potentials for a Sustainable Future

Sebnem Soher’s conversation with Diogo Dias Coutinho and Mariana Dias Coutinho of CLARA – Center for Rural Future focuses on the potentials of the Odemira region in welcoming creative and artistic practices to solve the issue of desertification of the area.

-

Public Cocoon

04.05.2023

04.05.2023