Urban Development through the Culture of Volunteering

Bilgen Coşkun and Dilek Öztürk talked with sociologist and Living Cities member Jennie Björstad, about social inclusion, “yes culture” and the role volunteers for urban development, after the “Co-designing Cities” talk as part of Curious Community 2019, organized by ATÖLYE and 3dots; in partnership with the Swedish Institute.

Can you please tell us about your background and how you developed your career?

I am a sociologist and have always been interested in the relation between individuals and society. I have been working with inclusion and equality from different perspectives, from international fair trade issues to public health and inclusion of marginalized groups at the local level. I experienced sometimes how “we” plan services and cities without asking what the people and user need. That’s how I found my way to Living Cities. The organization has a holistic approach to the relation between the social and physical aspects of the city with a focus on inclusion and co-creation.

Can you please tell us about the areas of work at Living Cities?

Living Cities offers new solutions for creating sustainable communities in Sweden and internationally. By working with the social aspects of urban development we want to create more inclusive urban spaces and alleviate differences in living conditions. Our areas of work include co-creative planning, integration and inclusion, mobility, collaborative cities, and pro-poor development.

How is your methodology shaped?

We listen to people and stakeholders. Our approach is based on the principles of dialogue, co-operation and transparency, focusing on the interaction between the physical and social urban environment. We partner with municipalities, governments, NGOs, housing companies and multilateral organizations to co-create more inclusive and livable cities. Also, we develop and explore our own areas of interest together with academia. An emphasis on gender, intersectionality, co-creation and innovation run through our work.

Equal Spaces project which is initiated by Swedish Institute is aiming for creative, smart and inclusive cities. You were invited to Istanbul in the scope of this project. What are the common values Equal Spaces and Living Cities share? How did your collaboration evolve?

Living Cities’ aim is to create socially sustainable cities, that is equal spaces. We believe in the power of citizens and that new ideas and partnerships are key to more inclusive cities. Our collaboration with the Swedish Institute and the Equal Spaces project was therefore very natural since we share the same values.

You gave a talk at Atölye about Co-Designing Cities together with Sarper Takkeci, architect and member of Herkes İçin Mimarlık (Architecture for All) and Onur Atay, architect and imeceLAB Coordinator. Which subjects were discussed at the talk? Can you please share the key learnings from the talk with us?

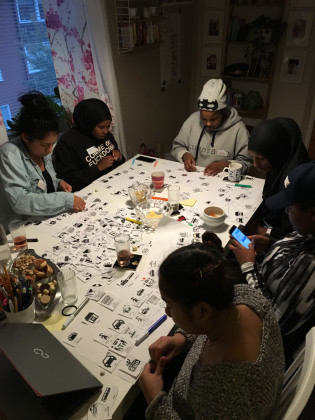

Often when we discuss socially inclusive, sustainable and equal urban spaces and planning, the concepts are quite abstract and sometimes seem to involve just anything “social”. In the talk, all of us presented concrete and practical examples on co-creation, co-designing and the power that evolves when people get together. We saw that the process to develop cities involves numerous actors and different strategies to partner with the public sector, residents, housing companies and NGOs; but also how citizen’s engagement could be powerful in itself. Inspiring to me was to learn about the role volunteers may play when it comes to co-designing spaces and urban development consultancy.

At your talk, you mentioned the importance of social inclusion and equality around different target groups in the city such as children, women, elderly people, etc. What are the main aspects of physical and cultural accessibility for a socially inclusive and equal city from your perspective?

The simple answer is that it depends since accessibility is contextual. But to start with, being aware of different dimensions of inequality can give us a lot of insights on who we are planning and building the city for. This means to involve people with different backgrounds in terms of gender, age, ethnicity, abilities and socio-economy in the process. When we listen to a diversity of perspectives, experiences and everyday habits, we will understand accessibility as something bigger than physical design and improvements. Then the planning process can include aspects such as public transport, opening hours, attitudes, safety, entrance fees, access to restrooms and privacy, what social activities are offered and in what languages.

“Co-building” and the “Yes Culture” concepts took an important part of your presentation at Atölye last week. (Open calls etc..) Can you please share your local/global experiences about “co-building” in terms of increasing the value of public space?

Often, participatory methods are applied in the planning phase and it may take many years of procurement and construction before the place has been built-up. But a pre-construction site is still a part of the city, and some cities have recognized the importance of using the space in the meantime.

The example I showed was from Gothenburg, Sweden. The city, architects and local NGOs invite residents to co-design an area which is to be exploited. No previous sketches or plans exist when the people meet up to create and build saunas and playgrounds together. In this way, identity and value are added to an empty space long before the permanent buildings are there.

Another case I presented was from one municipal planning department that decided to say “yes” to local initiatives as much as possible. The experiences are that when ideas are developed, accepted and owned by the citizens, it is more likely that it will give long term positive changes to the local community.

We see various lists of livable cities. What makes a city livable from your point of view?

Residents must have a good quality of life. A livable city is where people are welcome and able to live, love, grow, work and move. Planning and designing a place is an important part of the puzzle to enhance life quality. The physical design of the city may offer opportunities to meet and hang out in public spaces, encourage physical activities and make a place safer. Access to good education, housing, social support, healthcare, jobs and public transport are equally crucial to the livable city. This requires multi-stakeholder approaches and that’s why we emphasize co-creation and partnerships. I think that the Agenda 2030 goal to leave no one behind is key to this. We must always remember to ask who benefits here.

Related Content:

-

Hengqin Culture & Art Complex

-

Sana Frini & Philippe Rahm: Curators of the 2025 Versailles Architecture Biennale

-

The Orchestra Park

-

Ambiguous: Designing the Fictional

-

The Heart of Barrio de San Ignacio

-

Tianjin 4A Sports Park

-

The Children's Pavilion at the Serendipity Arts Festival 2023

-

Park of Memories Aš

12.06.2019

12.06.2019