The Elephant in the Gallery

Melis Uğurlu commentates on her unique experience of Elephant West, a gallery that relieves visitors from the fatigue of white cubes

During a recent visit to London, the city where I unapologetically subject myself to an intensive activity of museum-going, I was reminded by the notion of “museum fatigue”. This term was introduced by Benjamin Ives Gilman, in his 1916 essay with the same title, to describe the exhausting “amount of muscular effort demanded of the visitor who endeavors to see exhibits as museum authorities plan to have them seen.”1 Gilman’s criticism was directed towards the crowded and dense arrangement of artworks on the walls of museums that made it physically challenging and tiring for the spectator to absorb and view any work that wasn’t hung on eye-level. While this muscular fatigue was remedied at the end of 19th century when institutions increasingly began to isolate works in favor of giving art the deserved attention and avoiding overcrowding, it has also led to the emergence of a new kind of gallery aesthetic, and with it, a new kind of museum fatigue that is more psychological than physical.

The transformation in the method of displaying art, namely the abandonment of 18th century Salon inspired floor-to-ceiling exhibitions, did not only have practical consequences but also aesthetic. The interest in isolating and accentuating artworks left the museum and gallery walls emptier, opening up the discussion for their color, and eventually declaring “white” as the universally accepted wall color. This ubiquitous neutralization of wall colors also initiated a substantial change towards an overall abstraction, reduction, and minimalization. The walls and ceilings were painted white; windows were mostly sealed off; ceilings became the source of controlled lighting; decorative elements and ornamentations were either simplified or removed. Thus, the aesthetic of the “white cube” gallery was born.

White Cube was first used by the artist and critic Brian O’Doherty to describe this new neutralized gallery space. In his compilation essay “Inside the White Cube,” O’Doherty was also interested in drawing the relationship between the “context of the modernist gallery” and “what it does to the viewing subject.” Based on the indisputable observation that “we see not the art but the space first,” O’Doherty understood that, perhaps more than the content, the context has a certain effect on the viewers. He noted that “the essentially religious nature of the white cube is most forcefully expressed by what it does to the humanness of anyone who enters it and cooperates with its premises.”2

The experience of visiting a museum or a gallery is associated with a certain kind of behavior and atmosphere, one that is closely linked to the disciplining of space. We are not allowed to eat, drink, or touch anything. We are surrounded by security guards who occasionally remind us that flash photography is not allowed and we cannot cross over the taped line in front of the paintings. We are expected to keep full awareness of our surroundings, act properly, speak quietly, and move silently. It is a highly controlled, uncompromising environment that is governed by its own unwritten rules of conduct.

In pursuit of isolating the art, the gallery space has isolated itself. The disciplining of space and its self-defining nature has led to its detachment from the outside worldand anything that is other than its self. The grounds of neutrality that the modernist gallery space sets is in fact no more than a mere illusion: it addresses to a community and ideology of elitism and exclusion. The sterile, clean appearance of the white cube has made it equally artificial to the extent that our presence feels like an intrusion. And in the process, it disrupts our “humanness.”

We are bound by the careful limitations of this regulated space that swipes off any trace of context, history, or time. Windows, which “allow for discourse with outside,”3 are disinvolved and in a self-reliant attitude, the natural light is replaced with controlled lighting, resulting in total disregard of any sense of real time and real life. “The outside world must not come in,”4 writes O’Doherty, testifying to this atmosphere of disconnection. The white cube gallery is a powerful force of estrangement.

Participating in this space of neglect that claims power over its intruders evokes a certain feeling of discomfort and entrapment—psychological museum fatigue that one can experience in anywhere from the MoMA in New York to Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris to Tate Modern in London.

In the midst of this newly defined museum fatigue triggered by wandering numerous gallery spaces in London, I discovered a rather refreshing denial of the modernist white cube gallery: Elephant West. Located in West London’s developing area of White City, Elephant West is Elephant Magazine’s newly opened first physical art space. Already proving a commitment to inclusivity by expanding across the platforms of print, digital, and now physical, Elephant’s persistent theme of “collaboration” resonates vigorously in its physical incarnation as well.

Despite its vast grounds for attractive real-estate potential, White City had, in fact, remained surprisingly un-gentrified—until quite recently. The area’s ten-year, multimillion-pound redevelopment plan has now put plenty of construction and renovation on the horizon. Among these are BBC’s original doughnut-shaped building’s conversion to high-rise flats, the Royal Academy of Art’s new campus, and as of November 2018, Elephant’s art and project space. Next door to the former BBC Television Center, Elephant West occupies a previously disused petrol station, transformed by the architects Liddicoat & Goldhill.

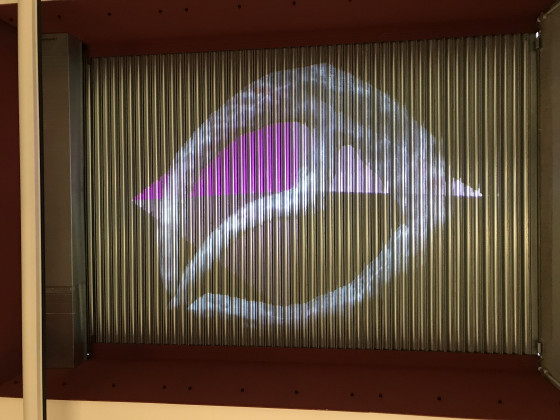

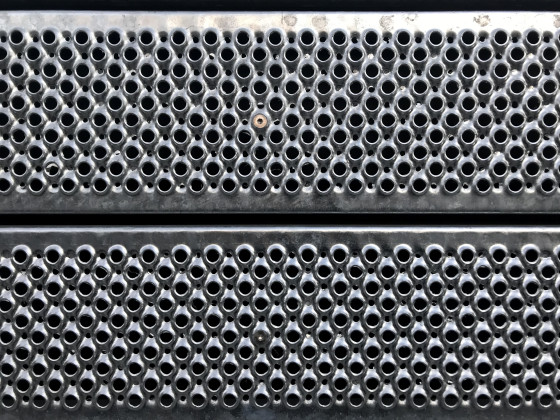

Both the interior and exterior carries remnants of its former industrial program and style, stripping away from the white cube aesthetic right off the bat. The yellow concrete bollards casually stick from the ground, the existing petrol pumps have a ghostly appearance through the polycarbonate columns, the rolling steel service door is utilized as a projection surface, and the exterior is clad in a pixelated steel scaffold.

Upon entering the space, I noticed that an open plan is employed, which allows all programmatic components to be laid out without any obstructions by the walls. It has the true feeling of a collective space that is comprised of exhibition space, workstation and seating area, a café/bar, and a small shop.

I first made my way to their bar, Fuel, to order one of their locally sourced drinks. After a short debate with the barista about whether this cold winter day in London deserved tea or alcohol, I settled on a chamomile tea with a shot of rum. With my drink in my hand, I moved to the seating area where I could see the exhibition and the paintings directly from where I was sitting. A young university student was studying at one of the tables in front of me. To my right, two girls were flipping through pages of an issue of Elephant Magazine at the shop stand. I enjoyed this scene of conjoint activities, taking a satisfactory sip from my chamomile and rum—my own personal attempt at non-segregation.

The non-segregation of spaces and diversity in activities has rendered the entire space so communal and connected that I was reminded, perhaps for the first time in a long while, that museums and galleries are in fact public places. While the white cube was neutralizing social space, Elephant was deliberately activating it. Elephant’s organization reinstates the gallery as a social space of interaction—both social and programmatic. Even the bathroom’s main door was, presumably purposefully, uninstalled; I could glimpse at the paintings while washing my hands.

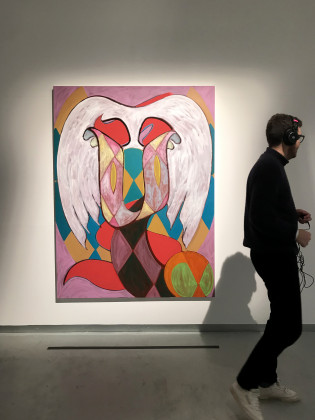

The current exhibition on display, “Muscle Memory,” was a further commitment to Elephant’s principle of collaboration. The painter Anna Liber Lewis and music producer Kieran Hebden (aka Four Tet) had collaborated on this project to create a multi-sensory experience. Hebden has produced three new tracks in response to Lewis’s paintings to be played during the show. This complimentary union of visual and aural spoke to the explorative openness of art, much like the context it was displayed in.

I left my drink before heading to pick up my headphones for the exhibition. Against the backdrop of Lewis’s expressive and emotional use of colors and gestures, I listened to Hebden’s mix that progressed from danceable and bass-heavy to atmospheric and ambient; and vice versa. In describing the restrictive attitude of classical modernist galleries, O’Doherty has explicitly noted that “one does not…dance.”5 Elephant West seems to have taken this on as a challenge and advised the “audience [to] feel able to move freely, and dance if they want to.”6 In what felt like both relief and rebellion, I tapped my foot to the beat, moving through paintings in a swaying motion. I felt free and immersed, and no longer an intruder.

With my headphones still on, I walked over to the seating area to enjoy a few more sips of my drink, still being engaged in the exhibition. I compared this experience to all the other museums and galleries that have asked me to move through multiple identical white rooms on multiple floors. Rather than segregated and multiplied, Elephant was united and overlaid. Rather than stiff and detached, it was flexible and inclusive.

“The best things in museums are the windows,” once told the French painter Pierre Bonnard to a friend as he left the Louvre for the last time.7 Windows in a museum are in the form of quasi-paintings that at once allow for a connection with outside and frame it as content. Bonnard’s powerful expression of the significance of real life to the content of museums can be interpreted both in regard to the exuberant sense of detachment one feels from the outside world and the inseparable relation between life and art.

As I left Elephant West, hopefully not for the last time, I concluded that while the white cube has a strong tendency to separate art from life, I remembered Elephant’s slogan, “life through art.” In this sense, Elephant West has succeeded in becoming the physical manifestation of its slogan. Whether it was this experience or the rum, my fatigue had disappeared.

NOTES

1Benjamin Ives Gilman, “Museum Fatigue,” The Scientific Monthly, vol.2 (1916): 62.

2Brian O’Doherty, Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986): 7-14.

3Ibid, 85.

4Ibid, 7.

5Ibid, 10.

6As of January 18, 2019, Elephant’s own website description of the event “Elephant x Anna Liber Lewis x Four Tet: Muscle Memory,” https://elephant.art/event/muscle-memory/

7Pierre Bonnard’s quote and background explained by NGA Education department, https://nga.gov.au/Bonnard/Detail.cfm?IRN=54552&MnuID=1

Related Content:

-

Bad Language: Architectural Snapshots by Max Creasy

-

Empath Door

-

Eurostar UK Terminal

-

Prix Versailles Reveals World’s Most Beautiful Museums List for 2025

-

Lee Terrace

-

House of Remembrance of the Augustow Roundup

-

15 Years of DesignTO: Toronto’s Festival of Joy, Justice, and Sustainability

-

Modern Guru and the Path to Artificial Happiness by ENESS Continues its Global Odyssey

09.04.2019

09.04.2019