Traces of Colonial France or Multicultural Paris?

In 1931, the last International Colonial Exposition of the world was opened in Paris. It was one of a series of colonial expositions that were held in France in the 1920s and 1930s, as France sought to reassert its colonial presence in the wake of World War I. In the opening ceremony, French actors underlined their particular attention on the conservation of local cultures in French colonies, and how they cooperated with colonized community rather than assimilate them since the beginning of 20th century. In his opening speech, statements such as "there is no racial class difference" and "we must learn to adapt to diversity" were strongly underlined by Marshal Lyautey in charge of the Moroccan Protectorate. In the European atmosphere of interwar period, this stance of French colonialist actors was a sort of justification for their continuous colonialist approaches. However, they have received only a few objections by French society in 1930s. Ironically, Marshal Lyautey’s colonialist approach was remembered again during the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020. Almost a century after his performance, which he pretended to promote cultural diversity, his statue in central Paris was vandalized.

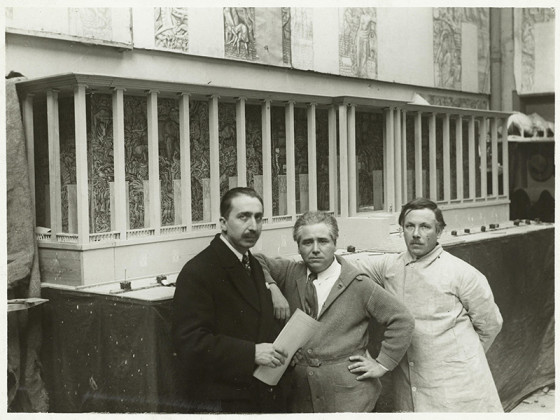

What made Marshal Lyautey important to 20th century architecture and urban politics? The book title "Lyautey as urbanists. Memories of a Witness (Lyautey Urbaniste. Souvenirs d’un Témoin)" written by Albert Laprade, prominent French modernist architect of the period who collaborated many years with Marshal Lyautey might explain a lot. Laprade was a Beaux-Art architect and he intensively collaborated with Lyautey since the announcement of French Protectorate in Morocco in 1912. This was the starting point of a long-term collaboration with French colonial politics with prominent modern architects. The combination of the desire of French politics to transform and control the colonial cities, and the willingness of French architects to experiment new technologies and developing modernist theories dominated the construction works of new buildings as well as the urban planning in Morocco. French architect-urbanist, Henri Prost was assigned as the head of Urbanism Bureau in Morocco in 1914. He formed a multidisciplinary group that contained engineers and architects. The plans prepared by this group were continued to be implemented until late 1940s. The group has been working strictly close with Lyautey both in decision making and implementation process. As mentioned by Laprade in his book title, he was directly involved in every segment of the processes related to urbanism as well as architecture.

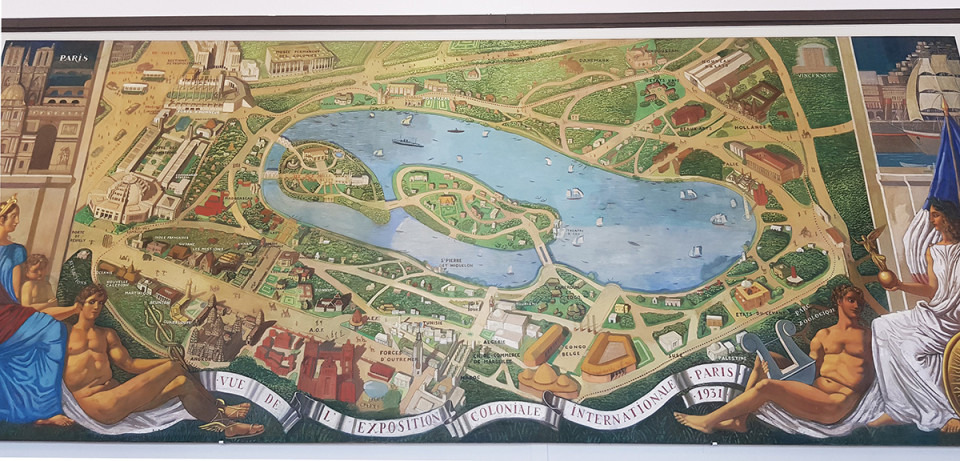

Almost two decades after the announcement of French Protectorate, the idea of organizing an International Colonial Exposition was emerged. Paris was familiar to international expositions, however, organizing a colonialist event in the core of historical Paris was not perceived suitable for the French politics. Significantly, a Parisian quarter in eastern part of the city, where the anti-colonialist protests were on the rise, was selected. The area was known as Bois de Vincennes, however, French writers started to call it "Lyauteyville (city of Lyautey)" when they mention about the exposition in printed media.

Permanent Monument of the Exposition

The main logic of the plan of Lyauteyville in Paris was the reconstruction of most famous historical buildings of the colonies. Beaux-Art architects were again in charge of these reconstructions. Many landmarks of colonial territories were projected and their miniature replica was erected in Bois de Vincennes. For instance, Angkor Temple of Cambodia was one of the well-known and most visited pavilion. Besides, the organization has arranged light shows during the night to attract the visitors in the entire day.

This big event remained open almost seven months from 6th May to 15th November, 1931. As many other expositions, the reconstructed pavilions were conceived as temporary constructions. However, the willingness of French actors to mark their "achievements" made the decision to construct a Colonial Museum as a permanent part of the exposition, a monument durable (permanent monument) as called by Lyautey. Even thought, French architect-urbanist, Leon Jaussely prepared the first proposal of the museum, Albert Laprade’s update of the architectural design was the final version of the implemented project. Jaussely’s orientalist ideas were combined with Laprade’s Art-deco style. This combined style was characterized by its use of geometric shapes, its emphasis on symmetry, and its use of bright colors. The building projected with four levels: a basement, entrance, mezzanine connected with the large hall in the entrance, and a second floor. The large hall principally conceived to host the inauguration of the entire exposition. Moreover, this large hall projected as an internal courtyard reminding the Moroccan architecture. Indeed, in the tourist information board prepared for today’s visitors of the museum, this idea is explained as "the overall plan is based on a series of Moroccan palaces symmetrically arranged around a central courtyard". This was actually the result of Laprade’s search to interpret the style in the colonies, combining it with the characteristics of the mother-country.

As it was a showcase of French colonial empire, the interior circulation of the museum was divided into two sections. Firstly, "Retrospective Section" was allocated to exhibit chronological and historical progress of national colonial movements from Croisades to 1912. Secondly, "Synthesis Section" was conceived to summarized the achievements of the French nation in this process. In addition, the organization of the entire museum was not projected only to list the colonial artefacts or movable objects. The organizers’ willingness to display the tropical nature of the colonies ended with designing the basement floor as a place where colonial flora and fauna can be exhibited.

Another significant point of the museum project was that two rooms at the entrance were designed for two prominent colonial actor of the period: Marshal Lyautey, and Colonial Minister Paul Reynaud. These two rooms, which can still be visited today, were emphasizing the presence of two powerful French men of the colonies at the museum entrance to the exhibition visitors in 1931. In particular, Lyautey’s room was designed to display the "spiritual richness of colonies" combining with the Art deco style furniture. The main aim was to reshape the originality of colonial atmosphere in this circular room dedicated to main responsible of Moroccan Protectorate and organizer of International Colonial Exhibition.

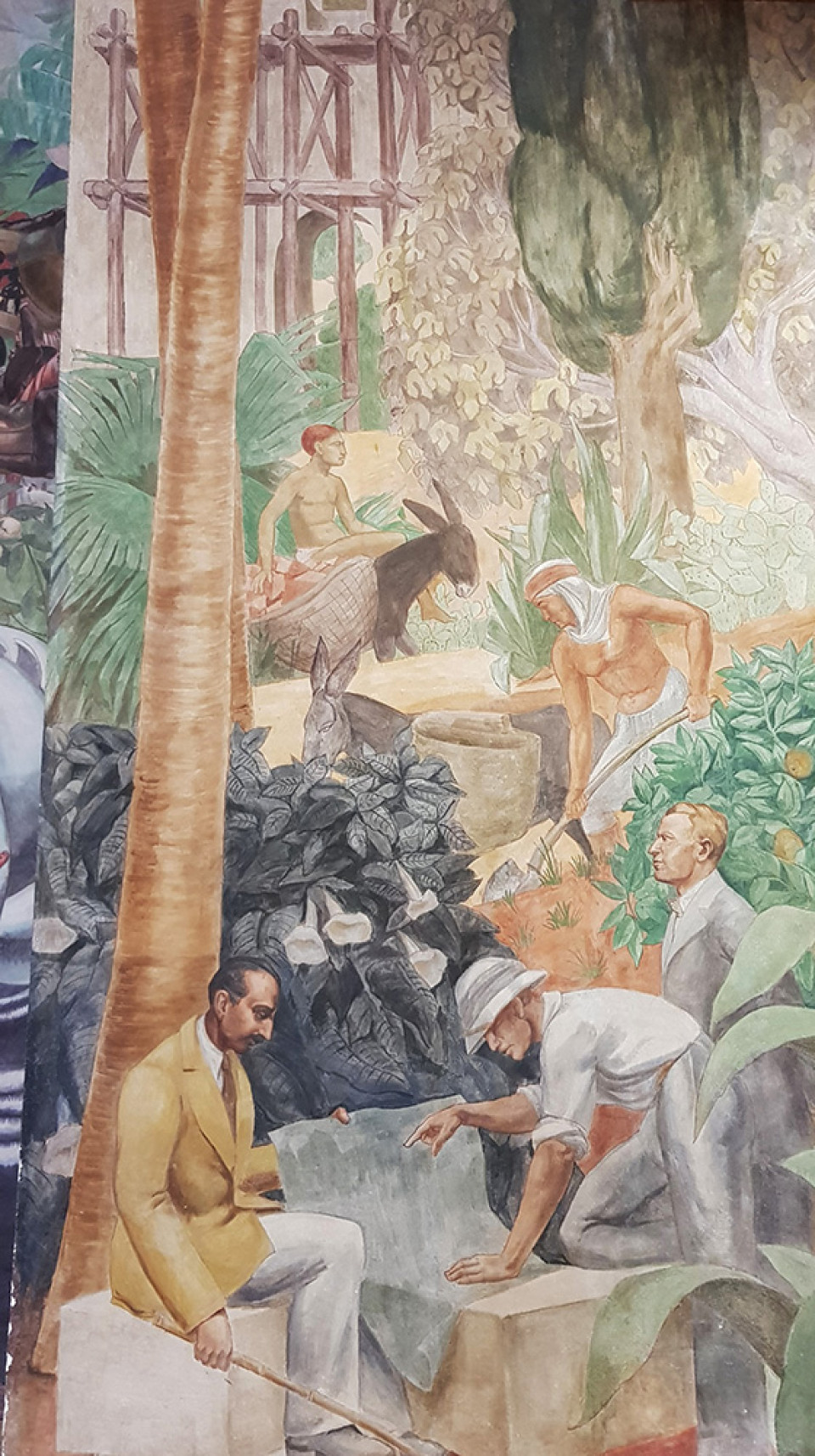

In line with the main purpose of the exposition which was to exhibit the "colonies" in Paris, the façade of the museum was significant. According to organizers, the façade should carry the representative aspects of the "Great France" which contains the colonial territories. The sculptor Alfred Janniot who collaborated with Laprade in colonies was assigned for the façade design. His bas-reliefs covered the entire façade by depicting the representative of colonial life with numerous animal and human figures.

The façade merged the colonial daily lifestyle representation by going beyond the Mediterranean colonies and reaching from Asia to Africa, from America to Oceania. Men and women of colonized community were depicted working in the fields with their animals, in traditional costume and even some dance moves. Fostering the power of mother country, France was allocated in the center of this panorama. This power demonstration dominated every segment of the museum. The all interior design was based on the colonizers’ intention to make visible of this desire. The walls were covered with the murals portrayed by prominent French painters. As an extension of external bas-reliefs, these murals combined the traditional life in the colonies once again by emphasizing the "civilization mission" of French. As highlighted by historian Gwendolyn Wright, the desire to make visible how this France brought civilization to the colonies so dominated the architectural project in every dimension that even the description of the building’s architect, Albert Laprade, examining the project while the colonial community was working in the jungle, took place in the main hall murals.

This 1931 colonial exhibition is also known as "human zoo" in the current postcolonial literature. The main reason for this was undoubtedly the bringing of local people from the colonized geographies they represented to the reconstructed pavilions. This local community lived in these pavilions during the entire exhibition period. They dressed with their traditional costumes, and tried to sell the traditional foods or artefacts during the day, performed their traditional music and dance during the night to Parisian elites. In other words, since the opening speech, this organization, which emphasized the policies that try to bring diversity to the fore by valuing respect and discourses in favor of conserving the traditional values in colonies was in a way an experimental performance show of this “diversity” presented directly to the Parisian elite. The representation of human and nature figures on the internal and external façades of the museum was a projection and permanent "memory" of the theatre written by colonial actors assigning roles to colonized community.

What do we see today in this "monument durable" of the exhibition organized by Lyautey, who is remembered again with the Black Lives Matter movement? Is the building erected for promoting self-congratulation of French colonizers still a colonial museum?

The answer is no with "but"… A few years after its inauguration, the museum shifted its name from Colonial Museum to Overseas France Museum. Under the European interwar political atmosphere, the elimination of "colonial" word was only first step of French desire to overwrite the main aim of museum project. The decolonization period paved the way for the museum to change its name two more times, in the following order, before taking its current name: firstly, Museum of African and Oceanic Arts in 1960; secondly, National Museum of African and Oceanic Arts in 1990. Lastly, in 2017, it received the current name "National Museum of Immigration History" known as also Palais de la Porte Dorée (Golden Gate Palace). The basement still exhibits the tropical fauna and flora with an aquarium. The permanent exhibition replaced with the synthesis of immigration history of France including all over the world countries. Moreover, the second floor is dedicated to temporary modern art and/or contemporary art exhibitions. The main hall hosts various of cultural events such as dance shows, workshops or concerts to promote the multiculturalism and to strengthen the awareness on cultural diversity.

It is undeniable that these events were held in front of the murals depicting French actors who civilized the colonies, creating an ironic contrast. In addition, each visitor entering the hall passes by Lyautey’s room, which is known for its racist policies and is still the focus of criticism today, is another entry of the contrast. However, it is clear that societies have changed many socio-cultural and ideological perspectives in the historical process. Single buildings and their architectural styles have always been perfect indicators to trace these changes over the time. For todays’ visitors who know the history of the building and the internation exhibition in its surroundings, a question stands on the outskirts of the Bois de Vincennes, east of Paris: Is it the legacy of the colonial France or the symbol of multiculturalism? The answer to the question may vary depending on the visitor’s point of view and personal interpretation of history. However, an architect can further question in lenses of heritage-led discourses and might ask: Why can’t it be seen as a junction point that has found its place in the historical process and reminds colonial legacy as a negative memory and supports a multicultural perspective? In other words, why not a monumental architecture that represents the neutral point of the two ends?

Bibliography:

- Laprade, Albert. “Avantpromenade à Travers l’Exposition Coloniale.” L’architecture, no. 4 (1931).

- Viatte, Germain, and François Dominique. Le Palais Des Colonies: Histoire Du Musée Des Arts d’Afrique et d’Océanie. Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2002.

- Morton, Patricia. Hybrid Modernities: Architecture and Representation at the 1931 Colonial Exposition, Paris. MIT Press, 2000.

- Morton, Patricia. “The Musée Des Colonies at the Colonial Exposition.” The Art Bulletin 80, no. 2 (1998): 357–77.

- Wright, Gwendolyn. The Politics of Design in French Colonial Urbanism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991.

Related Content:

-

So Wood

-

Atelier DARN Won the FAV 2024 Public Prize with RHUBARB

-

Leclercq Associés Unveils Revitalization of La Grande Motte’s City-Port Project

-

PONG: 20th Century Heritage Revealed By Its New Uses

-

The Aviator

-

Athletes' Village in Saint-Ouen

-

Exploring "Rhythm" at Festival des Architectures Vives 2024

-

Mixed Use Development in Gentilly

04.02.2023

04.02.2023