The Culture of the Ephemeral, Conglomerate, and Transient

Sex and the So-Called City exhibition investigates the factors that shaped the city’s urban lifestyle and cultural trends during late 1990s and early 2000s. Melis Ugurlu writes about the exhibition focusing on New York, which she describes as “an intricately layered playground”

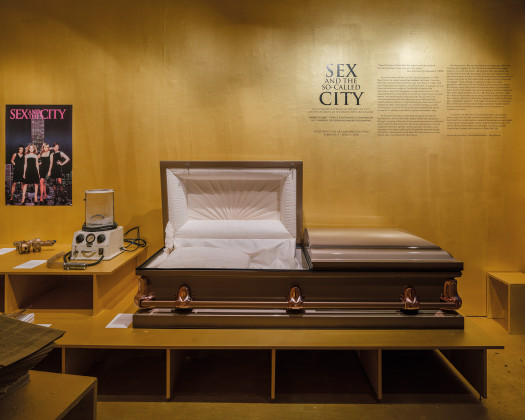

Andrés Jaque (Office for Political Innovation) in collaboration with Miguel de Guzmán (Imagen Subliminal) celebrates the twentieth-year anniversary of the show “Sex and the City” with a thorough investigation of social, environmental, economical, and political influences that played out over the course of two decades since the release of the show that have shaped the city’s urban lifestyle and cultural trends. The collaborated exhibition “Sex and the So-Called City” delves into various transformations the city experienced between late 1990s and early 2000s, from the booming of real estate development with shift to asset-oriented economy, to hyper-capitalization of society, to energy generation and reproduction.

Entering into the gallery space of Storefront for Art and Architecture where the exhibition is hosted is in fact quite analogous to the actual experience of living in this city: an undoubtedly small space in square footage, packed with all various kinds of content, accompanied by the loud honks of cars that penetrate into our interaction with the space as a background noise.

The exhibition is conducted as a transmedia narrative where artifacts of technological innovations, architectural components, and fashion objects sit next to one another in the narrow long space of the gallery: maps, fracking tools such as drilling bits and sensing devices that show the progression of the mineral domain, the Eckelt Lite Wall glass—the most expensive component of 432 Park Avenue building’s architecture—that is designed to “polarize natural light so the blue part of the daylight color spectrum is intensified,” photographs depicting pornography cinematography’s shift from grungy interiors to sunny open-plan condominiums, and replicas of the famous Manola Blahnik pumps, now sold widely on eBay for $59, that defined the fashion style for the city after Carrie Bradshaw appeared in them in “Sex and the City.” At the end of this sequence of objects, a documentary prepared by the curators and video bits from the TV series play on the loop, projected on a platform, the ceiling, and the walls of the gallery space.

Admittedly, the conglomeration of the superfluous themes and the introduction of various fields left my head spinning in search for pinning down the essence of New York City’s transformation during this time period. Then, I am reminded by the curators’ definition of New York as being “not a metropolis, but trans-scalar layers of trans-urban composition.” New York City is constituted of an abundance of influences. It isn’t single-handedly the architecture, real estate, economy, or media that determines the city’s urbanism but something else that lies in the intersection of all these components: the lifestyle and culture. Culture has completely hijacked the Metropolis and the city’s urbanism relies on its humans’ desires. New York cannot, and never will be, one thing, but if one thing is certain, that is that the city is in constant transformation.

At this moment, it is only inevitable to be reminded of the famous architect, theorist, and writer Rem Koolhaas’s retrospective manifesto on Manhattan, defining the city as a “metropolis of rigid chaos” and a “theatre of progress.” It has been four decades since Koolhaas coined “culture of congestion” to depict this island’s juxtaposed layers of lifestyles that is inherently a result of perpetual change, and this statement still holds true. The curators’ narrative on the transformation of New York City in 90s and 00s is not too dissimilar from the observations Koolhaas made back in 1978.

New York’s urban progression depends on a certain amnesia where the city reinvents itself almost every decade. The large population of the city consists of immigrants and there is a hunger for new experiences that is enabled by architectural and technological advancements. New York itself is a conglomeration of volatile humanist desires where its people, trends, and as a result the city impermanently changes.

In the midst of this urban competitiveness where the city constantly finds new ways to add layers to its urban structure, there is value in shifting our focus slightly away from Manhattan, just over the bridge: Brooklyn.

During the closing event of the exhibition, Cristobal Correa made the unavoidable remark: “If Sex and the City was shot today, they might set it in Brooklyn.” To borrow from the point of departure of the exhibition, “Sex and the City,” a later season of the show hints the, perhaps threatening, emergence of this alternative borough:

“And an upper east-sider went to see a house in Brooklyn.

Taxi Driver: Where to?

Miranda: Brooklyn. Please.

Taxi Driver: I don't go to Brooklyn.

Miranda: Yeah, neither do I.” (Season 6, Ep 16)

Once an industrial left-for-dead wasteland that taxis even refused to go, Brooklyn has become the epitome of post-industrial creative city that permanently aims to be temporary. Since declaring itself as an independent city in 1834, Brooklyn experienced numerous changes from new zoning laws to residential growth resulting in yet another urban juxtaposition of high and low. Especially beginning in the 1980s when artists arrived as pioneers, Brooklyn has always been a place of urban rebellion where legal boundaries are bended and an appetite for alternative is never lost.

What is archetypal of Brooklyn to a city in transformation is that it evokes the culture of the ephemeral, the transient, and the indeterminate that relies heavily on the synergies between different uses and spaces. We are already living at a time where shared economy constitutes the basis of our urban lifestyles that is less concerned with ownership and present an ephemeral ground for temporary use and space. Airbnb transformed the real estate, Citi Bike and Uber changed our relationship to transporting around the city, and WeWork claimed that we did not need our own office space but a community created from the culture of “come and go.”

Brooklyn has successfully taken this pop-up culture and brought it to an urban level. The uses of space do not own the space, rather the activities tap into spaces at the vacant hours of their original use and disappear once they are over.

The period when numerous high-rise residential towers emerged in Manhattan as a result of the city rebranding itself as a location for billionaires has been defined as “Highendcracy” by the curators of the exhibition. Brooklyn serves as a counterpoint to this high-end urbanism in various aspects of its urban composition and lifestyle.

In neighborhoods like Bushwick, it is widely common that the residential use occupies the spaces of the commercial. Due to prior loose zoning regulations, the large artist population owns studio spaces in commercial buildings where they also choose to live. These commonly seen commercial and manufacturing lofts are identified as incompatible for residential use by the city boards yet to accommodate its users’ lifestyles, undergo legal conversions to meet the safety and code requirements for residential use.

This symbiosis between different uses and spaces are evident in other occupational interactions as well. The art and music scene of Brooklyn is not necessarily restricted to the possession of a singular physical venue, but rather embrace the pliability of the activity as being able to take place in any “borrowed” space. The “secret location” of underground Brooklyn parties—be it an abandoned industrial warehouse, a boat, or the basement of a clothing store—is announced via a text message a few hours before the party begins, borrowed in the “after-hours,” and safely returned to its original use come the rise of dawn. The use holds the power to adapt easily to any space and the physical venue is infinitely changing.

As music is found in the underground, art is also found on the streets. Unlike in Chelsea where the clean white walls of galleries become a host and a background to artworks, in Bushwick, it is the streets that the art chooses to live in.

There is a distinct cultural difference that exists in Brooklyn that is raw, hidden, and transient in comparison to its “high-end” neighbor Manhattan. However, it would still be rather too simplistic and naïve to draw a clear binary between Manhattan and Brooklyn, defining the former as “high” and the latter as “low.” Parts of Brooklyn has also been invaded by the “high,” as high-rise condominiums start to appear on waterfronts of Williamsburg and Greenpoint. Such interplay between different cultural shifts is perhaps the essence of this culture of juxtapositions and congestion we experience every day in New York’s urbanism.

In the renowned sociologist Saskia Sassen’s words: “studying the city meant studying the major social processes of the era.”* The “Sex and the So-Called City” exhibition opens the conversation up for unraveling a multitude of these social changes that the politics of the city is built upon. Whether it is these transurban synergies that fabricate a new society or the society that impacts urban developments may still be up for discussion, but it is certain that the city’s constant transformation and complex network is fed by these continually changing interactions. A few decades from now, there may be another book, TV show, or an exhibition covering New York and we probably will be talking about much different narratives and players. New York will remain as an intricately layered playground for unpredictable and temporal changes.

*Saskia Sassen, “How Jane Jacobs changed the way we look at cities,” The Guardian, May 26, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/may/04/jane-jacobs-100th-birthday-saskia-sassen.

17.05.2018

17.05.2018