Falcon House

Designed by Italian architecture studio PAT. with architect Ferdinando Fagnola, Falcon House rises among the canopies of acacia and baobab trees on Manda Island, overlooking the ancient city of Lamu in Kenya. The office describes the project as follows:

This house is a testament to the harmonious fusion of local culture and innovative construction solutions, reinterpreting elements of tropical modernism.

• Falcon House gracefully emerges from the ground, creating a separation from the wildlife that may not always be accommodating, while also embracing the gentle winds that provide natural cooling among the treetops. The construction is designed as an environmental system that seamlessly integrates the surrounding landscape into the living space, resulting in a continuous interplay between nature and the interior living areas.

• The house embraces contemporary forms and materials that engage with local culture without succumbing to exoticism or contrived traditionalism. Involvement of local artisans and businesses fosters a collaborative and harmonious approach.

• The project is driven by a passion for the glorious history of steel construction, particularly the experimentation of modernist masters like Raphael Soriano, Pierre Koenig, and Craig Elwood, upon which Andrea Veglia, the founder of PAT., has long drawn inspiration. This approach leads Falcon House to unexpected and sustainable solutions that perfectly align with local conditions.

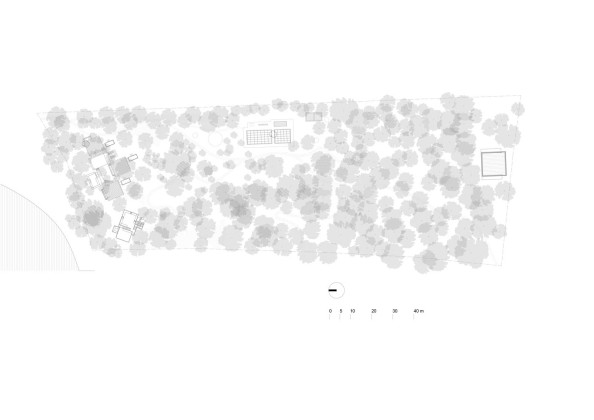

Falcon House is situated on an island without electricity or running water. The project by PAT. architetti associati in collaboration with Ferdinando Fagnola for this residence on Manda Island, overlooking the ancient city of Lamu in Kenya, is ingeniously designed to harness the forces of nature and adapt to its conditions. The architectural layout of the house consists of separate, raised rooms, allowing the prevailing winds (the Kaskazi, blowing from the northeast between December and March, and the Kusi, blowing from the south between April and September) to naturally cool the rooms, eliminating the need for air conditioning. Electricity, generated through photovoltaic panels, powers a desalination system, converting seawater into potable water for domestic use. Rainwater collected in tanks also contributes to the water supply.

An assembly of pavilion-style structures elevated from the ground.

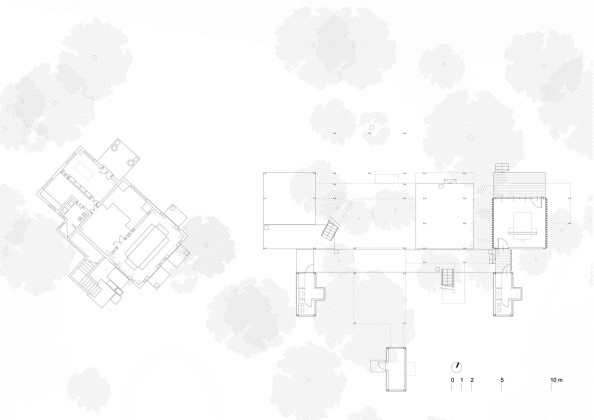

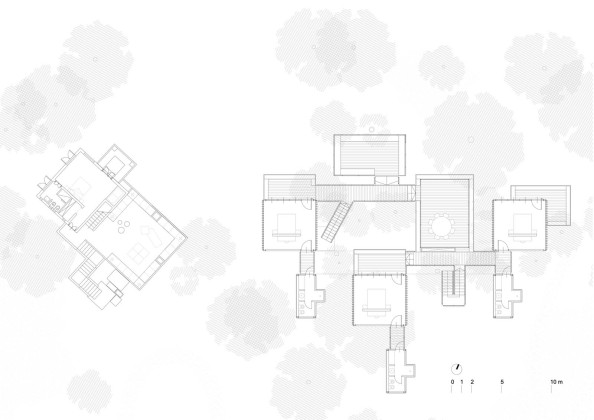

The house presents itself as a scattered assembly of individual pavilion-style structures, each elevated to approximately three meters above the ground on steel stilts, carefully positioned to harmonize with the existing acacia and baobab trees. In crafting this suspended landscape, PAT. and Ferdinando Fagnola initially explored a wooden structural framework. However, in a subsequent phase of collaboration with the owner, PAT. opted for a steel construction system. This decision not only emphasized the house’s distinctive design language but also ensured a more cost-effective construction process.

Recycled materials, construction techniques, and environmental quality.

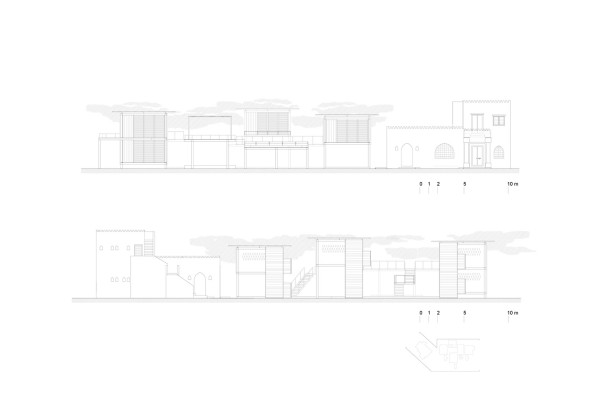

Pre-existing bungalows were disassembled with care, salvaging their wooden planks. The pavilions and terraces, situated at varying elevations, are connected by a straight walkway. Service and served spaces are distinctly separated, with bathrooms and wardrobes housed in turrets behind the rooms, linked by small bridges. The rooms, elevated to the level of the tree canopies, are shielded by a flat concrete roof, insulated on the outer layer, supporting a ventilated roofing system made of corrugated corten steel, designed to keep the rooms shaded throughout the day. The ceilings and floors are cast-in-place concrete, while the south wall is made from on-site prefabricated concrete blocks, created by local craftsmen using custom wooden formwork.

The shaded and ventilated concrete mass acts as a thermal flywheel, helping regulate the room’s microclimate, with adjustable wooden slats on the east and west walls. Four large pivot doors allow the north facade to open onto the sea-facing terraces. The adjustable louvers allow for the control of natural light and ventilation. This adaptable and manually operated climate control system, developed in close collaboration with local artisans, was the result of various mock-ups to arrive at the chosen solutions.

External decks and the bathroom tower cladding feature reclaimed wood from on-site structures and locally abundant, renewable eucalyptus wood, avoiding the use of over-exploited species like mangroves. Iroko wood, known for its durability, was selectively used for sunshade fins to ensure the system’s longevity.

“Our experience of sleeping in the old white house on-site was that it became unbearably hot at night, as its mass released the heat accumulated during the day. We had to resort to sleeping on the roof for relief. This experience prompted us to raise the new house on stilts, bringing life among the treetops and breaking up its volume into pavilions and terraces. This design allows for cross ventilation and eliminates the need for air conditioning. The rooms are sheltered by corrugated metal canopies and fitted with adjustable wooden louvers, creating a simple yet effective climate control system,” wrote architect Andrea Veglia, founder of PAT.

The original house and the utility building.

Falcon House was built alongside the renovation and expansion of the original mid-20th-century ‘white house’ in the Swahili style of Lamu. The white house seamlessly integrates into the pavilion system and offers sheltered living spaces on the ground floor, including a dining room with a large cast-in-place concrete table, a cinema room, and a library. The utility building, an independent pavilion situated behind the residence, was demolished and reconstructed on the same site. It houses the kitchen and now incorporates the new technological core of the house, which includes a photovoltaic rooftop, a battery storage room, a desalination system, and a water tower.

The client.

Falcon House is a distinctive presence on the island’s coast for various reasons, not limited to its design. The client, an heir to a Milanese family deeply connected to the city’s history and the Italian fashion industry, is a passionate contemporary art enthusiast who spent summers at the family house in Sardinia. However, what truly captured his imagination were other houses – those designed by Ferdinando Fagnola and Gianni Francione in the 1970s, recently renovated by Fagnola in collaboration with PAT. These brutalist shells blended seamlessly with the coastal topography, nestling among the vegetation and granite, disappearing entirely from view from the sea. Years later, when the client wished to construct a house in Kenya, he felt a strong desire for a profound connection with the land, reimagined within the equatorial environment. This led him to commission Ferdinando Fagnola himself and PAT. After a collaborative conceptual phase, PAT. successfully brought the project to completion, incorporating contemporary forms and materials that could seamlessly blend with the natural and cultural surroundings, avoiding any hint of exoticism or forced traditionalism.

Utilizing local knowledge and experiences.

Falcon House was brought to life through the collaboration of a network of local expertise and experiences. The project represents a blend of designers who are sensitive to cultural and environmental conditions, seamlessly integrating a variety of sensibilities from both local and distant contexts. PAT. harnessed local resources and expertise to develop sustainable solutions, addressing both innovative aspects and the preservation of tradition.

This new project by PAT. is entirely off-the-grid, accessible only by sea due to its isolation from any infrastructure, including roads. The house represents a dedication to complete energy and technical self-sufficiency. It draws inspiration from the beach houses designed by Craig Ellwood and Paul Rudolph, with a particular emphasis on research regarding steel-framed residential architecture, microclimates, and natural ventilation—research influenced by the work of Pierre Koenig, who has been an influential figure for Andrea Veglia since his early studies in California. Falcon House reinterprets valuable insights from a sometimes forgotten modernity with which PAT. maintains a close dialogue.

Notes on the materials and technologies of Falcon House.

(PAT., excerpt from the project report)

The selection of materials and technologies plays a crucial role in shaping this vision, influencing not just the architectural language but also tapping into local expertise and resources. This approach is firmly grounded in the principles of circularity and sustainability, encompassing both its innovative elements and its respect for tradition.

For the structural system, wood was initially considered. However, during the construction phase, the challenges of sourcing FSC-certified timber in the required sections and the high cost led to a serious consideration of steel construction, which was initially seen as impractical. While steel is not commonly used in residential architecture in Kenya, several local manufacturers offer systems of prefabricated houses with a hidden lightweight metal structure behind a traditional façade. Standard hot-rolled profiles are typically used in industrial and infrastructural constructions. The general contractor readily approved the change to steel, which led to fewer columns, extended spans, enhanced spatial flexibility, and resolved concerns about fungi and termites. This change resulted in a 30% cost reduction and a departure from any potential vernacular style. The steel structural components are fabricated in a workshop just a few kilometers away, transported by boat, and assembled on-site.

While visible steel structures in residential construction are a novelty on the East African coast, the use of corrugated sheet metal for roofing is not uncommon. What sets this apart is the context: here, sheet metal serves as the primary building material, a versatile and democratic material used for everything from shanties and shelters to warehouses. Its application in a villa is unusual, where it is recognized for its dignity and elegance, reminiscent of the homes designed by Glen Murcutt in Australia or Albert Frey in California. In constructing the external decks and cladding for the bathroom tower, eucalyptus wood, an abundant and renewable local resource, was chosen, in addition to reclaimed wood from the dismantled existing structures on-site. This approach avoids the use of endangered species like mangrove, which are overused. The stronger and more resilient iroko wood was specifically reserved for crafting the sunshade fins to ensure the system’s durability. Local craftsmen employed two-centimeter opposing and coupled boards to fashion counterbalanced slats, ensuring long-term dimensional stability. The entire wooden wall system is adjustable and manually operated using mechanisms inspired by simplicity and meticulous attention to detail, including pins and sliding handles made of wood.

Within the different volumes, the southern walls offer both shelter and promote ventilation. They consist of custom-made concrete blocks, manufactured on-site to match the thickness of the steel columns. These blocks are intentionally spaced apart, forming a pattern of openings that allows air to flow through the interior spaces. Tradition is expressed through the use of ‘niru,’ a smooth stucco finish that complements the clean lines of the new structures, adorning the walls, masonry elements, and even the interiors of the more traditional buildings, conveying a sense of solidity and intimacy.

Climate control, instead of relying on complex mechanical systems, is achieved through the structures’ orientation, shading, and natural ventilation, returning the project to the traditions of tropical modernism that have been overshadowed by the widespread use of air conditioning.

Electricity required for all domestic uses, from water purification and heating to lighting, is provided by photovoltaic panels. In this context, the utility building adjacent to the house plays a fundamental role: it is a “machine for living in, and living well,” with architecture that combines energy production through panels covering the entire roof and resource procurement, completed by the water tower.

The quality of Falcon House does not stem from the use of precious materials or refined imported technologies. Instead, it’s a testament to the abilities and passionate work of local artisans, technicians, engineers, carpenters, and craftsmen. They demonstrated remarkable flexibility, openness, and initiative while collaborating to devise creative and ingeniously simple solutions to meet the demands of this unconventional project.

07.02.2024

07.02.2024