Centre for Rural Development

Built at the edge of a rural landscape ravaged by illegal quarrying, the Sharanam Centre for Rural Development enables a local NGO to expand its transformation of chronically underdeveloped villages outside pondicherry, India

Meaning “refuge”, Sharanam was conceived following the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami to host community programmes in education, health and poverty alleviation. In this scarred context, the architect Jateen Lad sought to create buildings of dignity and tranquility while addressing pressing social and environmental concerns in the process.

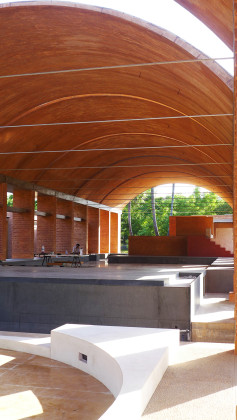

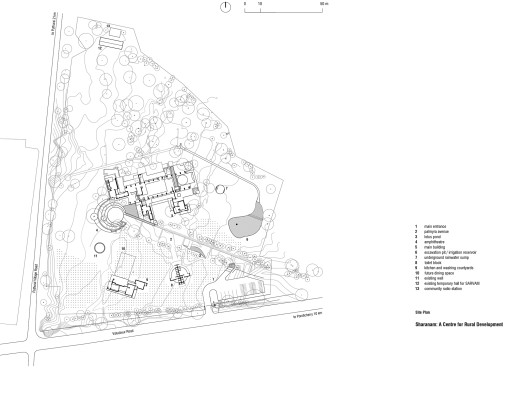

Sharanam comprises a large vaulted multi-purpose hall, meeting spaces, offices, newspaper studio, radio station and a community kitchen on a 5-acre site now healed and revived through extensive plantation. An entrance sequence leading through eucalyptus groves, an avenue of palms and a shaded amphitheatre reveal glimpses of the buildings.

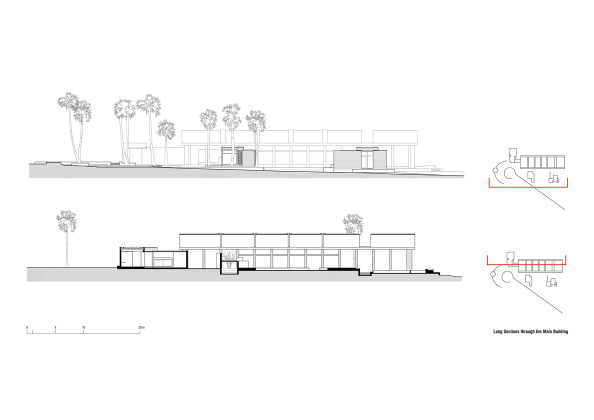

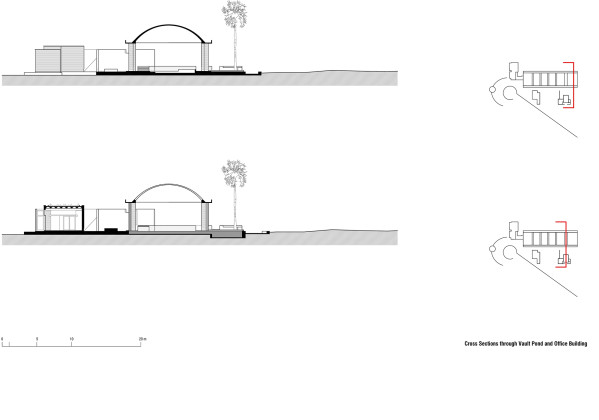

The project is constructed from the most local of resources – the red soil of the site from which over 200,000 earth blocks were manually pressed before curing under the hot sun. The superstructure utilizes self-supporting techniques to build an array of extremely thin masonry vaults, spanning 9.5m, over a sequence of distinct gathering spaces created by folding walls, level changes and ornamental ponds. Stone slabs step down into a hall defined by a massive granite thinnai – a raised platform inspired from the Tamil vernacular - which is scaled for small groups, workshops for 50-60 or an audience of 200. The thinnai extends to form a stage beyond which a smaller circular hall is set out under the detached eastern vault.

In response to the hot and humid climate, the open array of piers funnel coastal breezes into the building ensuring thermal comfort without air-conditioning or fans.

Deep verandas connect to office buildings with long minimalist walls, full-height teakwood glazing, cool-to-touch earth plastered walls, pigmented flooring and insulating roof gardens.

Entirely hand-built with only rudimentary tools and without a contractor, the construction was set up as a development project upgrading the employable skills and livelihoods of over 300 local village workers who were trained on-the-job in precision blockmaking, masonry, metalwork, precasting, carpentry, stonework, flooring and finishing techniques. This procurement route ensured over 50% of the construction costs were directly invested into the villages through wages. Today, previously unskilled workers are employable in the construction industry with many undertaking lucrative, professional contracts.

Through this approach Sharanam has aimed to demonstrate how architecture working from the bottom-up can help foster sustainable social and economic development.

Related Content:

-

Jackfruit Processing Unit and Community Centre

-

Enso House II

-

Cocoon: Pre-primary Extension at Bloomingdale International School

-

Project IronMan

-

Behind the Scenes | Artist Sujathan Scenic Gallery

-

Big Top: The Circus Canteen

-

The Stoic Wall Residence

-

The Children's Pavilion at the Serendipity Arts Festival 2023

14.02.2017

14.02.2017