A Poem to the Poor

“The PC takeover of architecture is complete: the Pritzker Prize has mutated into a prize for humanitarian work,” wrote Patrik Schumacher on social media, following Alejandro Aravena’s win of the Pritzker Prize.

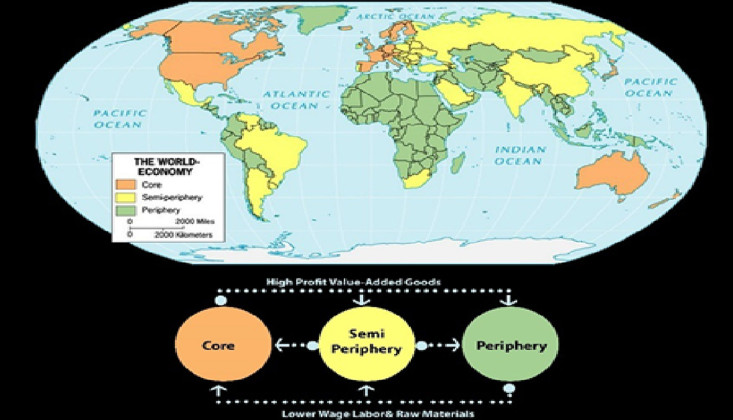

Architecture is has been questioning, and subsequently redefining its own social position and social role for almost a century now; with the world gradually becomes less and less secure through economical, political and social crises. When Marxism realized with the Soviet Revolution fed into the avant-garde utopian climate of the 20th century, the field of architecture thought it could free itself from the dominant economic, political and ideological pulls, forming instead a new social and historical role for itself by getting involved with the victimized working classes. What served as a wakeup call to the unrealism of such expectations were the Soviet state revisions: following the Lenin era, the dreams of a classless society were shelved and there was a quick acceptance of a state socialism of police force/military/bureaucracy. In the current state that it was, state socialism had nothing to offer to architects who were then searching for a new role. A fresh breath of air came from the Chinese Revolution that occurred in the middle of the century. China, after the revolution, severed its ties with that state formality which founded its legitimacy in capitalism-fueled economic success, and took on a new political role as the leader of the upcoming Third World countries that were late to the capitalization and modernization processes. The new block led by China was not only about belated capitalism however; it also included an anti-capitalist streak with the involvement of the likes of Cuba, Korea, Vietnam and South and Central America with their social and political struggles against capitalism. This new energy initially awakened the searching dissidents of First World capitalism; but soon lost its intellectual allies when it became clear that the “Culture Revolution” of China was not to bring independence to the culture, but simply more oppression.

Among these allies were the architects in search of renewal, and social-reformists who had realized that construction reforms in the both capitalist (First World) and state-socialist (Second World) countries had come to the same conclusions.

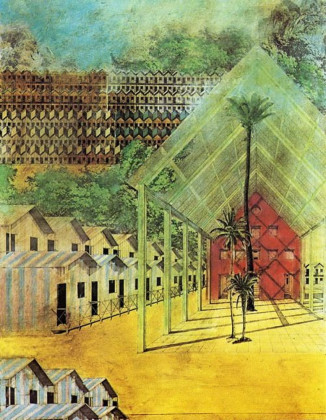

When expectations failed due to the Soviet determinism and the roughness of the Chinese cultural revolution, the informal shanty house practices were introduced to the agenda of the disappointed architects as alternative solidarity experiments to the formal capitalist housing market that could not meet the needs of the massive housing problem occurring in various places from America to Asia, from Africa to the Middle East.

The architectural design competition for Manila, the capital city of the Philippines, was a cornerstone practice in the 1970s that tested how much the architects could bring to these solidarity practices. This intellectual streak did not only come from John F. Turner, a technocrat from United Nations with social reform arrangements, but also from the mathematician Christopher Alexander, who, a long time ago, foresaw the potential of shape grammars of today’s digital world. Alexander was searching for a way to establish a language from the popular factors shaping the constructed environment. Despite tendency of academicians like Mehmet Adam, Erhan Acar, Yıldız Sey, Atilla Yücel towards social engagement, Turkey’s shanty house practices failed to reflect properly on the global agenda. Turkey came to produce its most unique text on the shanty house practice not in the academic field but in literature, with Latife Tekin’s writings in the 1980s: Tekin’s expression was not the expected product of a social, realist language that came from the village, but of the fairytale tone which the world came to recognize with Gabriel Garcia Marquez as “magic realism.”

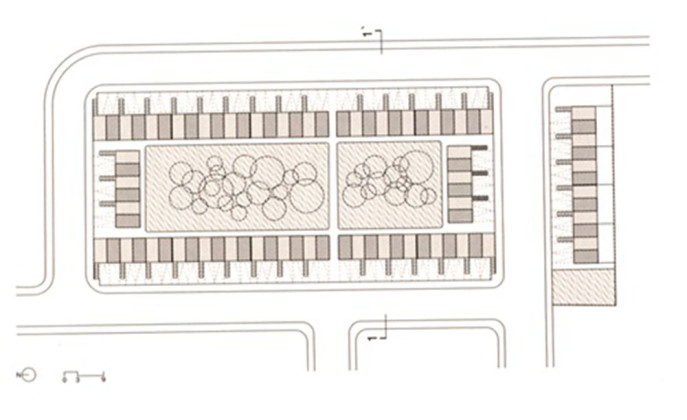

Getting back to architecture, what negates the discussion initiated by Patrik Schumacher, one of Zaha Hadid’s partners, over the contrasts between social engagement, architectural project and construction style, with its untimely emergence, is neither the revival of the already worn-out dilemma over form and context, which was driven into the pages of history by the constructivism of 1960s; nor was it the inaccessibility of the meeting of Turner-Alexander, reaching similar points through socially engaging and contextual motivations, to the residual contemporary history. Moreover, Schumacher has a fundamental weakness that prevents him from first seeing himself what he showed us. I think what he already missed due to barricades of his own form engagement even before starting the debate is the remarkable contribution of the Pritzker-winning Alejandro Aravena to architecture via his Quinta Monray project, in Inquiquie, Chile.

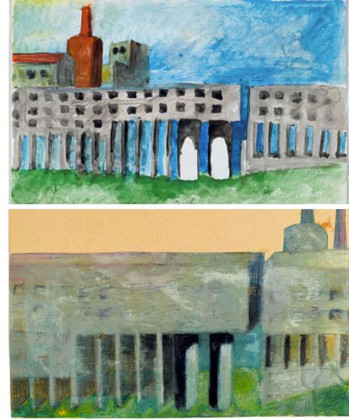

Let me tell you: The political-social dynamism in the Third World was not the only energy that nurtured the first post-modern wave of mid 20th century. The USA-based populism of capitalism and Europe-based elitism were also generating energies that would renew the field of architecture. The most noteworthy architectural-intellectual topic of the time, the Italian-based New Rationalism, brought a breath of fresh air by liberating the architectural language and defying the demanding categories of reason to transform the existed repertory of the constructional-architectural shapes into a poetic language. The ways of social solidarity coming out of the Third World had not yet crossed paths with these architectural memory channels with roots in the Mediterranean.

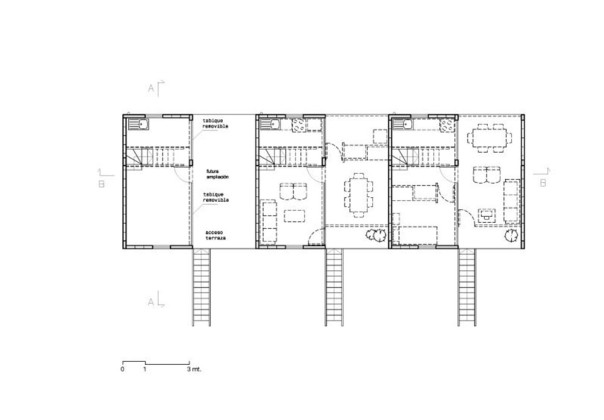

What makes Aravena’s notable Quinta Monray unique is not only the project’s obvious social engagement; but his way of holding on to that engagement by expressing a Rossiesque Mediterranean lyricism, both with simplicities and dramatic exaggerations, to bring forth the neighborhood.

The project nullifies the conservative compromise of right and left ideologies on how an intellectual lyricism cannot touch the reality of poverty, and how the sensitivity of the First World escapes the Third World; I strongly believe its architect deserves to be crowned, even if it’s only for the project’s defiance to ideological manias that we take to be inevitable. It will be up to dear Patrik now and his followers, who have shaped a position by shutting themselves off to this mixing of values, to linger about in their world of conformist shapes.

Related Content:

-

Riken Yamamoto Receives the 2024 Pritzker Architecture Prize

-

Participatory Design is the New Black

Cities are complex organisms that are able to develop themselves at an incredible speed and in different conditions.

-

Architecture Ablaze

'If cold, then cold as a block of ice. If hot, then hot as a blazing wing. Architecture must blaze.'

-

Reframing the Social

Hülya Ertaş talked to Florian Koehl on the social agenda of architects today and the alternative ways of realizing projects within the existing social and economical framework

-

Building Common Ground: Architecture of Game Changers

Architecture For+With+By Refugees is an open source online platform that explores and shows ideas, projects, buildings, workshops and open calls including refugees from worldwide

-

Unlocking Architecture’s Potential to Invest in Future

Engin Ayaz and Christian Benimana of MASS discuss how architecture should function, as well as looking into the facts of social design in Africa

-

Inhabiting the Earth in Symbiosis with the Environment

Aixopluc takes on the challenge to find new modes of inhabitation in symbiosis with planet earth

-

Where Will This Road Take Us?

The 21th century, due to constant crises and wars erupting worldwide or at least to our access to information on them, is moving forward with a sense of pessimism and indifference

22.04.2016

22.04.2016