New Forms of Conviviality

Basing urban transformation on active citizen participation, Lacol invents new forms of conviviality with people. Hulya Ertas talked with Cristina Gamboa, one of the founder members of Lacol, on their approach as an architecture cooperative

Hulya Ertas: Lacol was founded in 2009, right in the middle of the financial crisis here in Europe and around the world. What were the first ideas that you had when you were starting off as an architectural cooperative?

Cristina Gamboa: In our final year of university, back in 2009, we started to run this space as a kind of co-working space to work on our diploma projects. The idea was to be quite critical with the university because all the final projects were either extremely utopian, or they were focusing on super huge facilities and developments that would not have been possible in that moment. On the other hand, we were trying to work in relation with the neighborhood, mobilizing people to do pilot projects there. And two of them had become real projects. It was the beginning of the final project of one of the members of Lacol, and he had started with the neighborhood. He was working on the building program, and on people’s needs, through a participatory process. And then the neighborhood really wanted that kind of a facility, so the municipality started a public competition. Now that facility is built, and it’s been working since summer 2017. So it has been almost seven years—from the project and on. And it is same with Can Batlló. There were three of us working on Can Batlló. I think that was the transition that changed everything. When we started working with a neighborhood association, we realized that Can Batlló was one quarter of the neighborhood area that has been vacant more than 30 years. And this association has a strong community, which was involved in strikes and various movements at that time. It was like, “wow!”. In Can Batlló, people from the neighborhood associations have been working for the neighborhood for at least 15 years. They prepared everything but finally it was not necessary, we had the keys from the municipality, they made the cession of the space because of the community-power just at June 2011. In that process, everyone used the kind of skills they had. For us, it was our skills in architecture. As one neighbor said, we had the technical skills, and we agreed helping to decide on which one of the blocks inside Can Batlló was more interesting to start doing activities on. And we also really wanted to make this possible with all the materials, and our skills, through which we could create potential for the people.

And at that time, when the economical crisis was in its peak, starting an architecture practice seemed hard, but experiences as Can Batlló made us think about our discipline’s role in real-estate development and speculation, and be interested in a collective construction of the city by the citizens. Here in the neighborhood, there is a cooperative that consists of sociologists, anthropologists and researchers who conducted a research about social and cooperative movement in neighborhoods. They always say that these ideas are utopian, but when you have architects in the team active in the neighborhood, things can become real; because we really work hard to materialize those ideas.

HE: I know it is a bit kind of an old-fashioned question, but as an architect, how do you see your position in these participatory processes?

CG: I think, in our case, in all these kinds of processes we are working in—it is really a self-management process. So it was really a bottom-up experience, and we could see all the people organizing themselves through dynamic decisions, taken in assemblies. We are a part of the process, with a commission. For example, in Can Batlló, we took part in the general assembly as a neighborhood, and then we started to participate in those spaces that we felt useful: part of the team that negotiated with the municipality, the commission space-design and urban scale design. So in these three commissions there were also people who were not architects. The idea was being part of the movement, but we were not the leaders in any case—we were just like the others. The power came from bottom up, so we are not taking the leadership.

HE: How does the design process go on? I mean, you get the brief from this assembly I think, or you just think that we need this stair and so on. How does the process go on after that?

CG: Can Batlló was very experimental. It was like a laboratory. We learned a lot of things from that experience about working with people, building with people and with our hands. We also understood how use the resources we had, like recycled materials. It was a way of learning about all these, because we did not do any of these back at the university. In that moment, the assembly had different commissions. In the commission for the design of the space, it was decided to start with the library and then move on to the bar. So we did the general plan of the first block. We decided on the main points with the assembly, and then we did a workshop with people who were involved with the project. We decided with the commission, and worked together with them every Saturday. It took more than a year and a half to make the library, and then the meeting-point with a entrance space, a big stairs to connect the second floor and the bar.

We had a grant from Col•legi d'Arquitectes, the architecture association in Barcelona, for the design and construction of this space. In that case, all the work was voluntary. And also, in some moments the municipality, the district also hired us to do some part of really technical stuff. But most of our implication in Can Batlló was conducted as neighbors. I think it might be also the key—we were not from the municipality, we were giving our time as the others in Can Batlló. I think that experience was interesting to understand and learn about participatory processes. After that we could really work as professionals in these areas.

I think working in this kind of process with people from different ages and backgrounds has changed our minds. All of them were really political, with a long experience in self-managed spaces and social movements. Can Batlló was a huge area with different agencies such as private investors and local municipality officials working in the negotiation commission. So, we understood how and with which agencies the city transformation goes. We were working with the neighborhood and we were going one step further as we went to the official meetings, we had the ideas and we had the support of the people. The number of people in Can Batlló was growing, and it was transformed into a critical mass. We had started renovation with Block Onze, and there were different blocks on the same street. Then the gardens, special places for dogs and the theatre, etc. evolved. It has grown a lot since 2011.

HE: But it was occupied even before 2011, right?

CG: No. We started in 2011, when all the area was private. In 70s the area was planned to have private and social housing, green area and some facilities for the neighborhood. But the owner, a private real estate company was in charge of the transformation, so we had to do the urban design and facilitate some plots for housing. But, with the crisis starting, they did not want to build it and the transformation was stopped. In 2009, the neighborhood association declared that if investors and/or municipality were not going to do anything, they would enter and occupy to premises by July, 2011. It was a kind of tick-tack strategy with a certain deadline. Through that year we were doing a lot of activities, where we had huge numbers for the counting down of days. But in the same year, in May 2011, the spring movement in Plaça de Catalunya started. And the owner was scared of the power of social movements. To avoid a new mobilization and occupation just one week before the deadline, they started negotiations and established leasehold of one of the blocks to the neighborhood association. In 2011 all the area was still private, so during the first years the main part was turned into public in legal terms and the private plots were defined. Now all the area had change a lot, the municipality is planning the park, and developing three big facilities and almost all the social and private housing has been built. So it has been a really long process.

At the same time, the neighborhood platform had developed more and bigger project too, like La Borda (housing cooperative), Coopolis (a social economy and cooperative's incubator) and a school with an open and alternative education system. I think now there are more than 30 commissions and projects, and a lot of people involved. Sants is a neighborhood with a really strong network. In Can Batlló I think they all came together, had been a space of confluence and diversity, and also the first self-manage experience for others, you could see a 50 year-old women dancing in one block, and in another someone would be doing self-construction, or for example there were people from the neighborhood who did not know where to walk their dogs and ask for a part in Can Batlló’s open area. Now they have a biggest space for dogs in the city, self-managed, and really clean.

HE: Now Barcelona is being governed with people coming from the social movement Barcelona en Comu. Does it affect your work positively?

CG: In a way, yes. In one hand, they have developed interesting social policies and projects, like cooperative housing that we support and work for its implementation too. And of course, they also increase a lot the citizens participation to decide on urban matters, for example we worked in the participatory process developed to decide what to do with an old prison in the middle of the city, or we took part in the coordination for the new housing agenda which included a participatory processes in different districts, to talk about the needs, options and solutions with people in these different areas which totally different situations. On the other hand, we also realized that maybe we had politicians with a lot of good ideas and intentions, but the bureaucracy of the municipality is too strong. They have lots of difficulties in the implementation processes and it takes a lot of time to come over these, and also the technical stuff that had been worked out in the municipality do not always support changes. And of course, they are not the majority and there is a really complex political situation where all the parties are thinking more in the national rather the local context.

HE: I hear that a lot about the municipalities—that it is really hard to change the mindsets of the technical staff.

CG: For example in the cooperative housing project of La Borda, we worked for about 18 months to change the rules about parking. In our case, the cooperative knew the people who were going to live in La Borda. Most of the people did not have a car, so the existing parking regulations were obsolete in our case. There are a lot of references in Europe, when the parking areas and mobility in the city is being reconsidered in the municipality, but it took 18 months of discussions with the urban design department. And after that, there began a kind of change in some rules that were made during 70s. In a way, we started to change one part of the parking regulations. In the urban field we notice, four years is not enough to change the way of doing things. But it is a beginning, and we realized about the responsibility to be propositional in the transformation of our environments and cities, because it facilitates the approval of radical and courageous proposals.

HE: And also there is housing shortage in Barcelona.

CG: Exactly. We also do research about how Airbnb and these kinds of tourism projects are affecting the housing sector. You cannot stop Airbnb locally, and you cannot really make super big strategies to control these kinds of things. The solutions are not found locally. It is more about the global situation and the context of capitalism. And it is the same for a lot of cities. I think it is quite difficult for the Municipality of Barcelona to find the right kind of action against this path. Shall I invest in funds to buy flats to control the housing market? What can I do with this huge bisness of big boats arriving to the port? So at the end, it is more about this global system that understands cities as places to invest.

HE: And to consume.

CG: Exactly. I think it is really difficult for the municipality to stop these kinds of actions of a global connected and complex system. In Barcelona, the municipality stopped licenses for tourism flats, and also for hotels. A lot of people were against it but they did it. Even though a lot of people are critical about the housing prices going up and up, they still rent flats for tourists to get more benefit. These international investments are of course affecting the situation, but we also have to understand how small actions can change things. It is about our responsibility, again.

For example now a new organization is underway, Sindicat de Llogaters —syndicate for tenants’ rights. It is also interesting to see that the municipality can do a lot of things if they have the support of the people in the society and press from the inside. So they can do fairer laws. At the end it is kind of a combination. When people of Barcelona En Comu got the power in the municipality, some others had stated that we cannot leave all the responsibility to them. So, I think the organization of the people outside the municipality is really important. It is easy to say they are not doing enough. But each of us can also change things in the field of our lives and build relations with other ones.

HE: How did La Borda start? As far as I know, you have started a housing cooperative and got land from the municipality for free?

CG: Well, it was an old idea here in Sants. There was research about how a cooperative neighborhood could look like, how a self-managed neighborhood provide solutions to the daily needs of people, and Can Batlló became the place where put in practice all these ideas. In that context, 2012, one year after the entrance, a group of people from the neighborhood started to think about resolve collectively the need of housing through the implementation of a housing cooperative. So the idea was: we did a library, why not housing?

This group started to visit projects in rural areas and get in contact with other experiences in other countries, like Denmark and Uruguay. After more than a year of definition and consolidation of the idea, we started the negotiation with the municipality to have access to one of the blocks to restore it as housing but is was not possible because of the urban general plan. That relation within Can Batlló gave legitimacy and the municipality offered leasehold of a plot, instead of a block, for 75 years to develop the housing cooperative.

HE: La Borda was actually established with the people within Can Batlló.

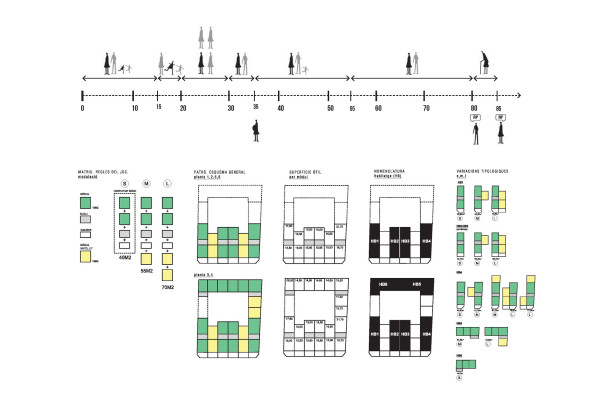

CG: Yes, exactly. In the beginning we were around 15 people related to Can Batlló. When the municipality offered us the public plot we realized that the project had to grow, and we did an open presentation of the project to the neighborhood in January 2018. It was a success, a lot o people were interested and joined the project: group increased to 28 units, around 55 people, 45 adults and 10 kids, all related to the neighborhood and its social movement networks. So there are people from different ages and backgrounds, and of different ways of living.

HE: Do you already know who is going to live on it?

CG: Yes. The group is consolidated since 2014 when all the process of development started. The members of La Borda control and develop the entire process through an internal structure that encourages their direct participation in work committees (legal, architecture, funding, conviviality, communication, administration) and a monthly general assembly.

HE: And did you design according to that?

CG: Yes. We consider the participation of future inhabitants and opportunity and had been integrated in all phases of the process: design, construction, management and use of housing. We started interviewing each member to know the profile, information about the unit composition (single, couples, co-habitation, etc), current housing tenancy, family incomes or mobility. We were surprised to see that a lot of people had economic problems, paying more around the 40% of the incomes for housing rent and they had also energy poverty.

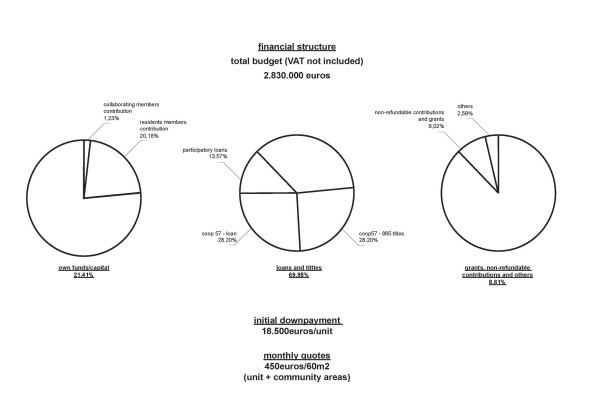

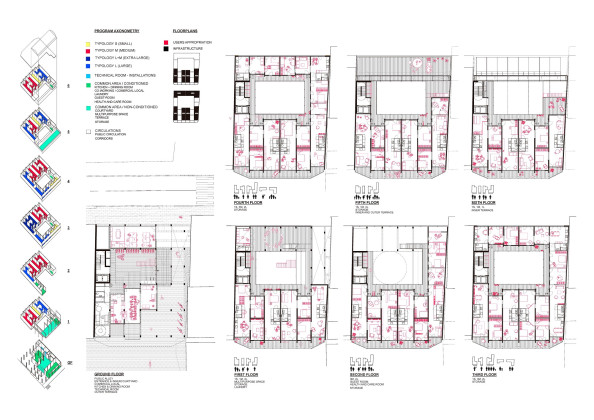

The main strategies of the project are based on the information from the user profile like the different typologies according to diversity of unit composition, the passive building to get comfort and reduce energy poverty as much as possible and work with a really low budget to reduce the mensal fee, and get affordable housing. After that, during all the design process we prepared workshops about imaginary, general strategies, program, environmental goals, typologies, materials, budgets, etc. It was really important for the community to imagine the collective areas such as common kitchen, co-working or commercial areas, and multi-purpose room, guest rooms, laundry and a space for health care (a place for the care of the body and treatments for the elderly). La Borda built housings to build community and it was something that you could feel during the process, which give much more sense to architecture. In the same way, all the members discussed about legal or economic issues, and defined the funding structures together that are also really interesting. We avoided the conventional banks, and worked with a financial service cooperative. The 20% of the funding came from the members of La Borda; and 70% came from this cooperative through loans and stocks. They issued stocks to the social economy network, so the funding was also collective.

HE: How does this membership process work with La Borda?

CG: La Borda is an open project, anyone interested can become collaborator-member through which gives the possibly to participate in the general assemblies. Now all the flats are adjudicated to future user-members, but in case you are interested to life in La Borda you can be added to a list of people expecting any vacancy that we call expectant-member.

HE: One of the things I noticed when I was looking at the projects was that it was about the materials, but also about the labor work during the construction. In the commercial sense, the architecture and construction industry is a dirty business. You know all the speculation, all the exploitation of nature to extract building materials and so on. I think it is really hard to keep yourself clean in that business of architecture. To what degree do you think you can control this?

CG: La Borda is kind of new development that wants to be also respectful in terms of sustainability. What we wanted to show people was that there were some values for building materials, especially in their environmental impact, and through choosing the right ones you can still be able to make a really low-budget construction. Because building with alternative materials use to be more expensive, we had to reconsider the layering materials or finishes. We decided to have a really good infrastructure; so we put the focus on the structure, on the insulation of the façade and all installations. The inside of the flats are really simple, because people can also improve those themselves to get things according to their desires or their personal choices.

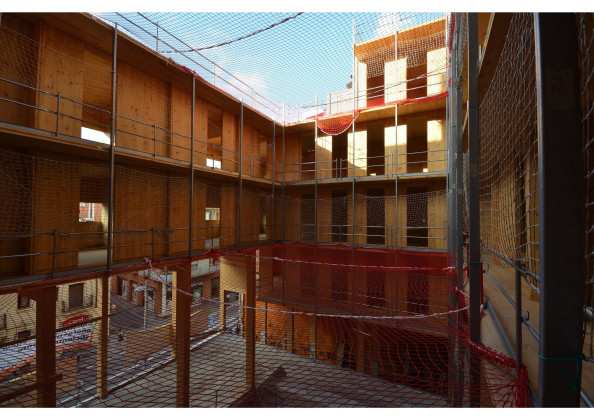

I think this project is interesting because our way of living is also sustainable. You share the facilities, and you have the central heating system, the communal laundry to save energy. So I think the way of living with these values of shared facilities also saves energy. In the cooperative, one of the main issues at the beginning was to work with an environmental consultant. It was interesting for us, because we worked through a lot of debates and workshops in the process. All our decisions had this environmental point of view. We used wood because it had a lower impact than concrete. We put a lot of effort for these passive systems. The atrium allowed the main parts of flats to have a good orientation. But I think it was more important to understand that what we were doing had huge effects in the life of the people and the planet.

HE: There is another kind of aesthetical understanding in these kinds of architectural practices, something directed more towards social concerns. Is it possible to define this new aesthetical approach? It has some kind of rawness and it looks unfinished in some ways.

CG: For one part, it was quite difficult working for the people who is going to live on these spaces, because they are used to see one kind of architecture, and for them what we were designing looked so raw and unfinished. So we had a lot of interesting discussion about the values and priorities, about what was really important when we are doing architecture. Are spotlights more important than the heating system that gives us comfort, or not?

We are doing the necessary things to start living. Any of these decisions are aesthetical decisions, because anytime we were going to do something more aesthetic, it was more expensive, that we had to give it up. So at the end, I think the result really has this idea of a new aesthetic, but this is not based on the desire of the architect. It is totally a consequence. And we like it, even more.

HE: Almost like the outcome of these ethical decisions.

CG: Exactly. You also have the context where you understand that there are the people, the program, and the budget. Also the regulations in Barcelona were, coming from 70s, very strict. So we had to be creative and find new paths to bend regulations. And there are also the aesthetic and environmental considerations, and so on.

HE: Who is doing the construction work?

CG: The main part is done by professionals. To reduce the price, the cooperative has a project manager and they contract directly these professionals. That requires a huge management. When it was possible, some tasks had been done by members of the cooperative. Once per months on Saturdays, people get together to work on different kinds of things. It is nice because you have a different relation with the construction, and you see things differently if you had done something for it. We can’t finish the whole project with the initial budget. The idea was to finish the flats first, and then start living there as soon as possible, and then start building the communal areas. It is interesting to see how people is going to appropriate of the space, the common and the private. It is a kind of open infrastructure that is going to be changing a lot. We decided not to define how the people will live, so we really avoided this kind of plan where you see certain spaces dedicated to bedrooms or living rooms directly and strictly—so strictly that you can’t even put the sofa in a different way. In the society there are structures that affect our living dynamics a lot, and we have to break them. And also our conviviality commission has shown examples from Copenhagen, where gender relation with housework is changing with the cooperatives. How can infrastructures change the dynamics between genders, or kids, or everything? I consider these discussions more interesting than construction itself.

HE: I think when you have minimum space which is your own, and a bigger communal space, then you also need to question what you own, because you can’t fill your minimum space with trash. I think these kinds of co-living projects also propose a kind of dispossession. Generally dispossession is a negative thing, but in these projects it is positive, since you don’t have to own everything, you don’t need to have too much for your own.

CG: Yes, exactly. It is an opportunity to redefine the life from different perspectives and possession is one of them. Actually, it is the essence of the project, the culture of property. Following the same idea of collective areas, we don't need 28 guest rooms, and we don’t need to buy everything because you can just use that item once a week from another resident. We designed spaces like a storage room at each floor where you can leave and share the vacuum cleaner, shopping cart... As the 40% of the units of La Borda are one-person-units, and this is a reflection of how the society is atomizing. All this discussions are even more important. If you are alone in a flat without any kind of community around, you are forced to buy and have everything. So it is interesting to see how this project gives an option to share in different levels and how our daily life is going to change.

19.09.2018

19.09.2018