Taking Care of Exhibitions: Notes on the 16th Venice Architecture Biennale

In a profound text called "On the Curatorship"1 the art critic and philosopher Boris Groys describes the art work being unable "to present itself by virtue of its own definition and force the viewer into contemplation; it lacks the necessary vitality, energy and health." He argues that "the spectator has to be led to the artwork" and reminds to the etymological relation of the word "curator" to the Latin word of "curo", hence to cure, heal, take care. Opposed to the recently increased popularity of the independent curator defining installations, exhibitions in the contemporary art world (and feeding the commercial art market therewith) the curator’s practice dates from the early nineteenth century when the museums entered the history of culture. Back then curators administrated collections and defined what can be considered an art work to be part of the museum. They also had to create narratives in order to draw a framework other than mere "collecting". These followed at first a chronology but around the turn into the 20th century narratives started to indicate thematic organizations among the chosen works. After drawing parallels between the autonomy of the artist and the (in)dependency of the curator Groys notes that the independent curator of today, however, would be a "radically secularized artist… who lost the artist’s aura, who no longer has the magical powers at his disposal, who cannot endow objects with artistic status. He doesn’t use objects- art objects included-for art’s sake, but rather abuses them, makes them profane. Yet it is precisely this that makes the figure of the independent curator so attractive and so essential to the art of today." This notion of "abuse" is embedded in the creation of the narrative to which the art work "serves". In this construction the role of the independent curator, be it vulnerable or not, is at least clearly about conceiving a narrative.

When it comes to curatorship in architecture the position of the curator is much less debated. Curators make exhibitions and exhibitions are in their nature controlled; chosen or commissioned works are put on stage to be scrutinized under a focused gaze. In the most ideal case the curator directs this gaze by not only choosing the works but also interpreting and grouping them. This is not an easy task; especially if, as in the architectural context, it happens mostly in the frame of biennales. Yet despite the increase of curated architecture exhibitions in institutions or galleries architecture is not as used as artistic production to the practice of curating. The claim that architecture can be best experienced if built, adds to the struggle about how to exhibit the production. Legendary exhibitions such as Weissenhofsiedlung from 1927 contribute to this view enhancing the importance of the experience based and pragmatic approach on how to exhibit architecture. The projects built under the artistic direction of Mies van der Rohe back then are still today to be visited. They were experiments with building techniques as well as new forms of living through projects realized by seventeen architects, which were considered then-a-days avant-garde and invited by Mies. His choice of those practitioners surely avoided conflicts of positions and later on, Mies was criticized for inviting mostly “fellow” architects. But the focus on the dwelling and urgent needs of the post WWI European society drew sharply the contours of the debate as well as the outcome.

It is not unusual that critics would refer to the Werkbund’s exhibition of nearly a century ago when they review or comment on the Venice Architecture Biennale, the most prominent architectural event of our times. In architecture the sensation of built material as exhibition content survives the time mostly better than any other form of exhibition. This also applies to some pavilions in the Gardens of Venice: To name a few, the serenity of the Nordic Pavilion by Sverre Fehn, the calm courtyard of the Venezuelan Pavilion by Carlo Scarpa, the once temporarily meant but by now the permanent Finnish pavilion by Alvar Aalto or the former book shop built by James Stirling never fail to attract the eye first to themselves. This, however, is sometimes counterbalanced through strong narratives reflected to the theme of each edition defined by an artistic director, a role which in the history of the biennale gradually became replaced by the word "curator". Different than in the artistic exhibitions though and except two editions only, Venice architecture biennales have been directed by practicing architects since its institutionalization in 1980. A sharp emphasis on the over spanning narrative rather than an overview of a certain architectural production was first introduced by Hans Hollein in 1996. Perhaps Hollein has been the pivotal figure on what would be called later the “curation” rather than artistic direction because of his proximity to arts and consideration of himself also an artist. Under him the 6th edition carried the title “The Architect as a Seismograph” and investigated the role of the architect as it would be a measuring device to sense vibes from the underground in order to react to them concerning the future. Hollein must have acted himself as the seismograph so that the show he curated personally in the Italian Pavilion became sensational and another one called “Emerging Voices” he dedicated to young architects at the time indicated many of today’s significant professionals.

Other editions of the biennale have not always enjoyed such driven attitude but reached sometimes an allover coherence with the announced themes. Meanwhile the scope of the event extended to many more countries, the participations reached an almost indigestible number. Every two years a different approach of an appointed curator defines the destiny of the exhibitions up to a certain extent. Obviously a too literal translation of a theme defined by the curator carries the danger of becoming too anecdotical. Yet this year’s theme “Free Space”, defined by the appointed curators Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara, literally offers so much space that it is very hard to find a focus. Obviously the theme can be interpreted in various ways but exactly there lays the danger that it can go anywhere if it is not well “taken care” of; and this is also what happens throughout the biennale this year. It is very apparent that mature practices contribute with stronger projects to the theme. A remarkable one is the participation called “The Island’”in the British pavilion. The curation of national pavilions respond with more autonomy to the general theme set by the main curators. The British project is a curatorial collaboration between Caruso St John architects and the artist Marcus Taylor. It touches many layers of spatial experience reflecting on a highly political, acute issue of Brexit. The empty pavilion surrounded by a scaffolding, which leads to the roof of the building and offers magnificent views over the Gardens and the laguna is not an anecdote. It is accompanied with a program of events and also, with daily ritual of the typical British tea-time. Not only the content but also the materialization of the huge terrace is “taken care of” and every detail -both conceptually and architecturally- has been thought through. With the title, the contrasting spatial experience between the emptiness of the pavilion and loaded surrounding visible from high up over this empty space trigger reflection on what is happening between UK and Europe.

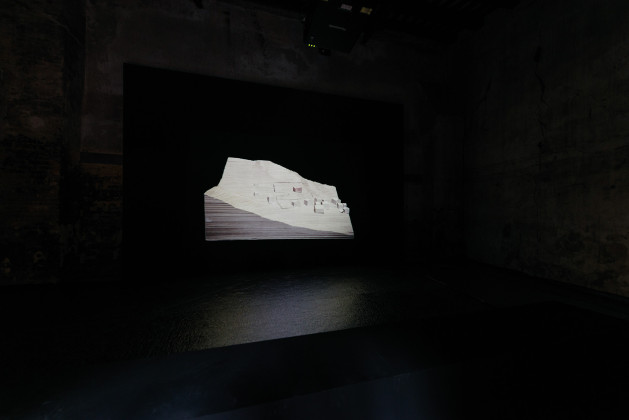

In a small, darkened room in the Arsenale and on a very different, modest scale Miller and Maranta architects from Basel take us to a journey of their mental space. They call it a ”thoughtscape” , “a vast topography of interrelated thoughts”, leaving enough free space to the spectator yet also keeping their authenticity in how they approach architecture. Fragments and objects are ordered in a projection, alternating with models of their buildings. They awaken memories and associations and prove the quality of the intuitive without becoming random. Miller and Maranta’s contribution shows a way of not only seeing but also approaching things, be it an object or a building. Highly individual yet very convincing in the interrelations between their thoughts their interpretation of the free space is both in its modest scale and layered content a sincere counter piece to “The Island”s relevance.

The sensation of the “built” comes through the Vatican’s first participation, which is curated by Francesco Dal Co and involved ten practices to build “radical” chapels. The incorporation of Christian idolatry wasn’t a requirement; here the space to be created could be free of any recognizable religious item in order to provide enough space for the human, whether a believer or not. The chapels are spaces, rooms for reflection, which should be engaged through architecture. Each of them are architectural objects on their own right and together they make a silent statement on what perhaps the society should strive for: enough free space to believe, or not to believe, to doubt or to commit. Perhaps here the “abuse” Groys mentions is most visible; a curator who interprets the theme of free space in the interest of the commissioner’s search for a more open identity towards the society. Ultimately both profit from the result, which provides strangely enjoyable spaces despite the clear position of the commissioner.

Notwithstanding these and few other contributions, the 16th edition of the Venice Architecture Biennale does not appear as a thoroughly curated event. It rather seems as if once the word ”free” has been allowed, the content could be spread on a vast, endless field of interpretations. The narratives start each time anew and the participants seem like the result of personal taste of the curators. As in the case of Weissenhofsiedlung, this diagnosis can be projected surely on many other curations of both architectural and artistic exhibitions. But in Venice, the lack of clear definition of the theme and even of some borders result in a show, which is more reminiscent to a fair of architectural production with an overview what is “going on” in the architectural world.

As Hans Hollein and Maksimiliano Fuksas jointly argued in an interview for Domus in 20042, an exhibition is not the translation of a publication into the third dimension. It needs a strongly controlled content, a story defined by the curator if there is a complexity of diverse production. The story does not always have to address an urgent, practical need or to derive from a historical analysis but it should convince in relevance. But if the opportunity is given to tell one about architecture the narrator should take this chance. Over nearly forty years, Venice Architecture Biennale has established itself as a generous platform, which deserves to be "taken care of" more attentively in its narrative ambitions.

NOTES

1 Essay by B.Groys, p: 43-52, Art Power, MIT Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-262-07292-2

2 Hollein vs Biennale. Biennale vs Fuksas. a contribution from Armin Linke For Domus: Rita Capezzuto, Hans Ulrich Obrist and Stefano Boeri Photography by Armin Linke , published on 29/9/2004. https://www.domusweb.it/en/architecture/2004/09/29/hollein-vs-biennale-biennale-vs-fuksas.html

16.07.2018

16.07.2018