Settling Day for Architecture: Venice Architecture Biennale

When Alejandro Aravena was announced as the curator of this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale, excitement and hope swept over many of us in the world of architecture. Let me say first what I am supposed to say last: Aravena does not let us down. Frankly, it exceeds my expectations. With its highly productive and creative main exhibitions, and national pavilions not only interpreting Aravena’s theme, but also raising the quality of the debate which he had started, the biennale is full of narratives of how the field of architecture can break the chains of the neoliberal economic system. The sincerity and courage in facing the truth, and the beauty originating from the directness of these narratives, are redefining what we know as architecture. The biennale underlines the urgency for the shift in architectural practices, which are today serving the private capital, continuing their “business as usual” approach, and working on commissioned projects. And it achieves that by showing the power of architecture in eliminating suffocating built environments, pacified communities, and crime generating—even fatal—spaces.

The title of the biennale is Reporting from the Front. Even though I had found this military word a bit strange at first due to its masculinity, Aravena succeeds in his battle metaphor. The profound question for the participants of the main exhibition is: “Which front are you fighting on?” Quality of life, inequalities, segregation, insecurity, the state of peripheries, migration, informality, sanitation, waste, pollution, natural disasters, sustainability, traffic, communities, housing, mediocrity and banality… This list of fronts placed at the entrance of the main exhibition at Arsenale perfectly summarizes the architecture of today. Aravena has requested the participants to answers three questions in the simplest way possible: What was the situation at the front (the problem); how did you fight (the process); and what did you win (the outcome)? Most of the teams have responded to this call and took their place in the main exhibition by employing easy-to-communicate tools such as tangible models and fluent videos. Aravena himself has also responded to his call and turned the introduction area of the main exhibition into a sincerity temple.

The exhibition layout, composing of recycled materials from last year’s Venice art biennale, proves Aravena to be not only a man with strong ideas and political views, but also an extremely talented designer. This gorgeous entrance must give chills to the well-off conservative architects who keep labeling socially-aware designs as lacking aesthetic capacity. In this introduction area we can see the texts of Aravena’s whatsapp group chat with his office colleagues, where he announces that he has been selected as the curator of the biennale; along with footage of internal meetings and biennale press conferences, the e-mail trafficking between Aravena and the participants, his dismissed proposals, and the initial version of his transformed theme text. With a smile on our faces we also watch the videos of his young colleagues setting up the exhibition with joy, and feeling the well-deserved and secret pride of their Chile, labeled a periphery nation, taking over of the center stage in the architectural scene’s most important event.

arsenale entrance exhibition, photograph: hülya ertaş

After you pass the introduction area you come across a small gateway opening up to the main exhibition. The gateway reminds me of the little door in Alice’s Wonderland. You enter into a world of imagination where everything is possible, leaving behind the corporate architecture that has been continually shaping our cities. Yet there is a slight difference: these projects are not figments of imagination, they are absolutely real. Aravena’s words at the press conference come to my mind: “Commercial architecture is the real villain here. These offices, with thousands of architects working for them, are there just to help private capital generate profit rather than contributing to the public good. And nobody is saying anything about it—all these firms with letters A, B, C, X, Y, Z. They still build over millions of square meters while we are debating here.” Aravena stands up against the widespread practice of transformative power of architecture forced only into the service of private capital at a time when social contribution is considered not to be part of the architect’s responsibility. He renders visible the architects and their projects who use this transformative power for communities, and fight for that power at the fronts listed at the entrance of the exhibition. Aravena uses his curatorial authority to discipline his own discipline; something that is considered, by Patrik Schumacher and the likes, as undermining the profession. Aravena incorporates the “criticism of the architect” into the criticism of architecture, and in doing so, invites us to take responsibility for our actions. It is normal for this to annoy some, especially architectural firm owners who are very fond of building all around the world while paying no regard to the social consequences—like Schumacher himself. (A small note on Schumacher: I bring his name up on purpose, since I overheard his video interview conducted at Venice. He was stating that the biennale should be closed down because architects, being experts in creating a future vision, cannot run the process if the public intervenes. What on earth does the public know about architecture anyways?!) The architectural scene has long been occupied with “starchitects” who say one thing and then do another. With this biennale, architecture gains a great opportunity to reconfigure its very being through openness, transparency, multiplicity and cooperation, rather than relying on professional chauvinism. Isn’t it more rational for architecture to channel its creative capacity for social issues rather than forcing the profession into boundaries, especially today, in times of widespread access to information? Even if we put aside society, isn’t this a wiser, more pragmatic and empowering choice for the power-hungry architects? Perhaps the conservatism of some of the architects suppresses everything, even their pragmatism, whilst making the choice.

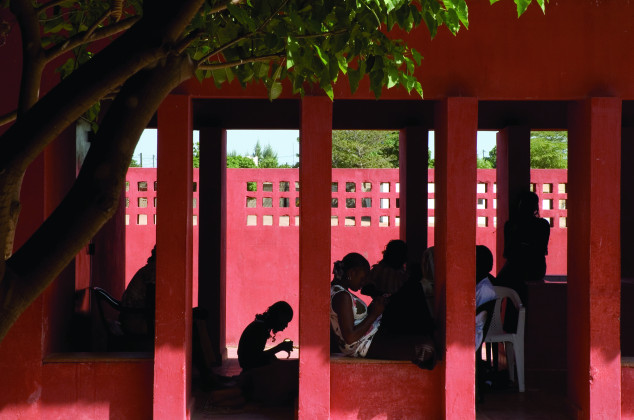

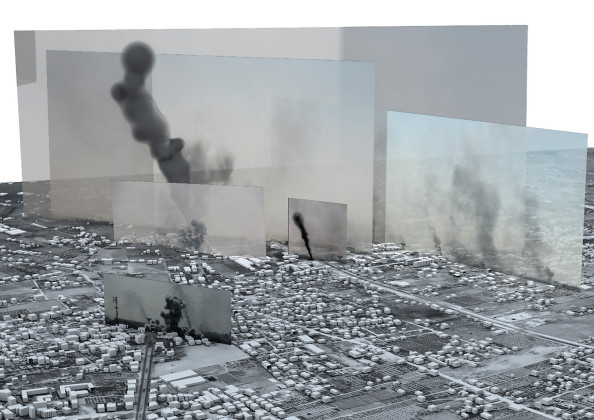

Let’s put aside Schumacher, who acts only as an extra in this biennale, and get back to our leading actor, Aravena. I have encountered, more than once, a sentence written in his rationale texts: “The problem is not poverty, but inequality.” The real problem is the unfair distribution of the resources, and the deprivation, or more correctly the forceful deprivation, of many from humane living conditions, despite sufficient abundance of money and capacity on earth. And architecture has to fight on that front, because by serving the interests of the private capital it further feeds inequality more and more, day by day. Aravena’s efforts, however, to prevent this biennale from turning into a humanitarian aid campaign or a requiem for the poor are quite evident. This biennale is not a call to the architects to gather and go somewhere in Africa to build with local materials and people. It is an invitation to all architects, who can see one way or another some kind of inequality around them, to do something in their very own context. This approach eliminates the distinction between developed, developing and underdeveloped countries; urban or rural areas; and reveals the globalized neoliberal policies as one of the most important fronts of architecture. And it does so through flesh and blood narratives in a very calm manner: a good restoration project, an evidence room showing how architecture helped the killings in Nazi camps, a museum built with durable materials that can stand for more than 100 years, a women empowerment center, a junction to help decrease crime by generating a lively market place, regenerated water tanks serving as public parks, reports showing military lies through spatial analysis, and many more… The battles fought by architects within their respective contexts frame the main structure of the biennale while making visible the communities, authorities, institutions and NGOs they worked with through this battle.

"more than a hundred years” by christ & gantenbein, photograph: stefano graziani

The context is such a determining force that any attempt to understand whether or not the exhibition focuses on certain geographies fails. Questions such as “Will we see many projects from Latin America, or from other poor countries?” become irrelevant. Aravena has gone after works where architects tackle the issue of inequality to widen the radius of action by multiplying the fronts. Assemble’s works in the UK, Wang Shu’s in China, Renzo Piano’s achievements as a lifelong senator for the Italian government, Rahul Mehrotra’s ephemeral housing solution for the world’s most crowded religious festival Kumbh Mela, David Chipperfield’s unembellished visitor center design in Sudan… These projects cope with the borderless neoliberalism through their own practices; and find means to overcome it in various great ways. Architecture not of countries, borders or passports, but of contexts, peoples and communities…

Contrary to the former Venice Architecture Biennale’s slightly obsessed Rem Koolhaas, Aravena has chosen to leave the representation of the works to the participants (or it seems that way), and in doing so, remains in the background. As a result, polyphony resonates in the corridor of the Arsenale, but not all of the participants succeed in communicating their works. There are some works that fail to comply with Aravena’s tripartite structure of problem-process-result by poorly representing the first two. This situation, however, may also be read as the outcome of the need for revision of architectural representation in our era. It is evident that altering the familiar representation of familiar forms of action will take some time. Nevertheless, one of the biggest successes of the totality of the polyphony of works in the main exhibition is the present determination of staying close to architecture, albeit in forms expressing a wide-range of concerns that the participants were dealing with. “Yes, we have a problem and it is a multifaceted one. We cannot solve it completely; but what can we do? Through architecture, what kinds of responsibilities and initiatives can we take on? How can we share this, with whom and through which platforms?” It is as if the biennale is seeking answers to these questions. And none of the works claim their respective answer to be the only correct one. Most of them were as modest as Sanaa’s landscape rehabilitation project for Inujima Island in Japan that hosts about 50 people. Improving spaces with to-the-point solutions is not considered enough; what we see here are realist utopias that allowed for conversations with communities and authorities with hopes of generating long-term processes. As the curator Aravena says, after seeing these works, there will be no excuse for architects to go back to their offices and continue their business-as-usual ways.

We all know that this is not the first time where working with communities, employing participatory processes and defining the responsibility of the architect are taken as the main agenda in architecture. It would thus be unfair not to mention the differences between Aravena’s approach and Cameron Sinclair’s, who inspired many architects through the first decade of 2000s with his firm Architecture for Humanity. Sinclair focused on geographies where access to architecture was very limited, and referred to “humanitarian architecture” as having more clients due to the vastness of earth’s poorer population. And this started a movement of architectural service that was exported in the form of a humanitarian aid. They had concentrated their work on places like Africa or Sri Lanka that suffered natural disasters like tsunami. A good architect was going to these places and realizing architecture. Sinclair was not thinking that inequality had spread all around the world, or it was that such a debate wasn’t too popular in the early years of the millennium. And this is exactly what Aravena adds to take Sinclair’s approach further. According to Aravena, if anyone was just to look around, they would see inequality surrounding them everywhere, and can start the battle by trying to figure out what to do; and in doing so, can multiply the capabilities and possibilities in generating solutions. An architect figure who does not function as an outsider expert looking at problems, but as one who tries to do his/her job as a reflection of his/her world view—without building walls between his/her existence as an individual and as a professional. This reminds me of what we learned from the Occupy Gezi movement in İstanbul: a sociality made up of individualities; and through this sociality, the wish to build a world where one wants to live in, with feelings of comfort and confidence in living in a social sphere, but also of responsibility and accountability. The biennale was a declaration of good days to come where work and private life, professional suits and pajamas, come together after many years, allowing the individual to define himself/herself as a unified whole again.

National Pavilions

To talk about national pavilions, we have to first make a categorization. Three approaches are apparent to the visitors: Those who complied with Aravena’s call and sought sociality in their own country’s architectural practices, those who ignored this call and committed instead to represent their countries, and those who took on the call but misunderstood it. Thankfully, in this listing, the first group comes up as the majority; the second a minority; and the third, marginal.

The pavilions that attempt to show the fronts fought in their respective countries, and by doing so take on Aravena’s theme to a local scale, raise the level of discussion. France, for example, looks at the small changes in daily life while defining the “new rich” and this is a perfect fit for France and a reminder of the legacy of Lefebvre. Chile recalls the importance of rural; showing works of students of architecture who has designed and applied small scale structures at their homelands—to which they will return to after graduation. In its pavilion where tote bags with Turkish store names and logos on and free ayran is provided, Germany proves it is not the first time they are facing a refugee emergency and defines its front through research-oriented works. Taking advantage of being an island and distancing itself from the refugee crisis, United Kingdom focuses on its own long term housing problem and seeks new uses of houses in the light of different time periods (hourly, daily, weekly, annually). Japan, another island, shows some contemporary designs that manifest the tradition of nature-friendly and human respective practices in the country; and the ambition to continue to do so, even under the threat of neoliberalism. Korea reveals its dilemmas in creating the built environment with great sincerity, and invites people to a game, sharing its problems with the international community even if they are not to be solved within this biennale. With papers scattered all round, Egypt questions the role of architecture in a place where media cannot spread the truth. The pavilion seeks how daily habits of people can be included in building the urban space, like a pigeon breeder’s contribution to ecosystem in the city. Denmark smartly says: “We, as architects have never put aside our social responsibilities and here are plenty examples of that.” Yet, alert audiences can see through this cacophony where even BIG’s projects are included and, say, “No, no! It was not the architects who cared about the social responsibility, it was the state itself.” Greece only represents ideas selected through a transparent participatory process from the very beginning, and hopes to amplify these ideas during the biennale. Yemen brings in the beauty of its demolished cities; Peru the new schools built at Amazons; South Africa its own experience in organizing a guerrilla biennale; and Thailand its convalescence after the earthquake—but Aravena’s biennale experiences no difficulty in receiving all these.

peru pavilion, photograph: andrea avezzù

The second category of pavilions, which have no relation to Aravena’s theme (and it was not obligatory to have one), undertakes the mission of representing their countries. The Australian pavilion, where you get to know about the country’s pool culture and put your feet in the water, must be the most irrelevant pavilion anyone sees during the biennale. Similarly, the Israeli pavilion shows some innovations at the intersection of architecture and technology. If we want to include those who aimed to be relevant to the theme but failed in doing so to this second category, we have to name Russia with its pavilion of anthems and statues; as well as Serbia, which was made up of a blue surface with electricity outlets for charging mobile phones. Victims of over-abstraction, these pavilions fail in delivering their messages and their thread of relevance to the theme disappears.

The last category of pseudo-relevant pavilions can be best described through the U.S. pavilion. It housed speculative projects “for” Detroit, a city that has for long been in decay since the automobile industry perished. The pavilion manifests a spooky celebration of architecture where form is at play and the city is suppressed by those forms. Solutions to Detroit’s social and environmental issues were commissioned to 12 expert architects; who in return, it seems, just sat down and designed nice “buildings.” One of the most prominent proposals is of a building block out of space, supposedly for the poor. Maybe the intention is to point to spaces where the poor live and to create a new example of spatial segregation. Although a group named Detroit Resists voiced warnings against such speculative design early on the biennale process, the curators of the pavilion clearly chose to ignore them. In short, the US pavilion renders itself as an outrageous show of the “greatness” of America.

Turkish Pavilion

The Turkish pavilion should also be classified in the last category of the pseudo-relevant ones—the ones that misinterpreted Aravena’s theme knowingly or unknowingly. This misinterpretation, however, is not surprising in this postmodern world of continuous rhetoric building. Rather than focusing on what was said in the biennale texts and the inner meanings of the end product, I will now try to look at Darzana through its process and its final result, and try to read Turkey’s presence in the biennale.

Let me describe Darzana: It is an installation made up of recycled materials at Haliç Arsenale, designed by Mehmet Kütükçüoğlu, Ertuğ Uçar and Feride Çiçekoğlu. The first two are running an architectural office called Teğet, that is also involved in the real-estate development project of the Haliç Arsenale. So the Haliç Arsenale development project and the biennale participation are inseparable as the authors are almost the same, since the biennale team was also composed of people working at Teğet Architecture. If Teğet wished us to read these two as separate issues, they should have come up with a totally different concept instead of focusing on this very specific site where they are also currently doing the development project behind closed doors. Teğet might be going through challenges with the client, similar to the fronts posed throughout the biennale, but these fights are not represented or included in the pavilion. Wouldn’t it have been perfect if they had just shared their correspondence with the client, or minutes of their meetings, and drawings of the project—just like Aravena does at the introduction of the main exhibition at Arsenale? But this cannot happen; since Teğet’s confidentiality agreement with the client guarantees development processes to be operated completely closed to access and with zero public participation. So, they have chosen to deliver an art installation instead, one they set up at Haliç Arsenale, dismantled and carried to Venice, with plans to take it back to Istanbul to display at the Halic Arsenale once their project is realized.

In the meantime, as it is displayed on the screens at the Turkish pavilion, Haliç Arsenale is physically closed to the public. Not only the public has no idea what the Arsenale area will look like, it is also impossible to get in there. Teğet has the upper hand in this since it would have been impossible for anyone else to acquire the materials of this installation. If someone, however, had come out of nowhere and stolen these pieces from Haliç Arsenale to take them to the Venice Biennale; and in doing so, told the story of the exclusion of the public from the development project process, it would have been a perfect fit for Aravena’s theme!

As a result of all these contextual shifts, what Turkey represents at the biennale does not go beyond mere “shape.” There is no doubt that this is a very beautiful shape, one of the better examples of ruin aesthetics that has been fashionable for the last few decades. The bastarda takes the ruin aesthetics further and becomes a fancy object as the inadequate pieces are painted in nice colors; and rather than being assembled, these hung from the ceiling in a bid to get rid of the possibly ugly junctions. In some ways, it has a nice correlation with the state of Istanbul.

The pavilion has one more feature that is not frequently mentioned, maybe because it does not photograph as well as the bastarda: the screens where you can see Cemal Emden’s photos of Haliç Arsenale and of the setting up of the installation. One watches these images in grief over the state of an industrial heritage, and wishes it to be open to use again. Since the biennale texts do not mention Teğet’s position, people unaware of the firm’s involvement in this reuse project may end up considering the Turkish pavilion as a representation of a “front”. And that is exactly how the pseudo-relevancy occurs. Just like the US pavilion (and we have objections of exclusion of the public from Haliç Solidarity, similarly to claims of the Detroit Resists), Turkish pavilion also relies solely on shape to represent itself, sidestepping the need for content, and in doing so, displays one of the fronts listed by Aravena: the banality.

Although Turkish pavilion occupies itself with the concept of overcoming frontiers, it fails to succeed, and remains as a reflection of the situation in Turkey. Unlike many of the other national pavilions where teams come together and generate multiplicities, ours becomes the country itself, where only one voice is heard—and even that voice is saying very little and concealing a lot.

turkey pavilion, photograph: cemal emden

Related Content:

-

"We Have To Think About What Progress Is"

Ponto Atelier is a young office from Portugal with works varying in places, programs and scales. They are based in Madeira Island, in the Atlantic Ocean and they are about to become much more visible soon, with several ongoing projects to be completed and their participation at “Fertile Futures” Exhibition, the Official Portuguese Representation of the Venice Architecture Biennale 2023, curated by Andreia Garcia. Şebnem Şoher talked to Ana Pedro Ferreira and Pedro Maria Ribeiro, founders of Ponto Atelier about their inspirations, being on an island and what it means to be sustainable today.

-

Open Call for Pavilion of Turkey, 18th International Architecture Exhibition of la Biennale di Venezia

-

Stories of Adaptation

-

Social Design for Beginners

Curated by Angeli Sachs, Social Design exhibition in the Museum for Gestaltung Zurich aims to discuss implications of growth economy on human beings, environment and design. Banu Çiçek Tülü reviewed the exhibition as a good example of inclusiveness in a country where democratic design processes emerge in urban scale.

-

Learning From Change

In conversation with Jan Boelen, the curator of 4th Istanbul Design Biennial on the theme of "A School of Schools." We discussed a variety of issues starting from the making of a design biennial up to design's capacity to respond to changes in the society.

-

New Forms of Conviviality

Hulya Ertas talked with Cristina Gamboa, one of the founder members of Lacol, on their approach as an architecture cooperative

-

Dignity of Social Housing

The most important question we have to ask is whether Robin Hood Gardens is really sufficient to meet today’s requirements. If not, would demolishment be the one and only solution to be brought up?

-

Seeking the Potentials of Space

What kind of contributions will Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara make to the architecture scene with this open-ended Freespace theme? This is something that we will see in time.

08.06.2016

08.06.2016