Acting and Making Collectively

Maniera searches new design proposals by working with architects and artists who blur boundaries between architecture, design and art

Emil Jurcan talks to Hülya Ertaş of XXI magazine, looking into the political and social problems of architectural and urban projects in Croatia. Jurcan's insight ranges from the privatization of military areas to public participation, as he explains the inner workings of the Pulksa Group and the Praksa Initiative

Hulya Ertas: You have been following up on the future of Pula after the demilitarization decision of the city. What were the plans of the authorities for the empty buildings and lots, and what were yours? As we are having a similar problem here in Turkey after the failed military coup attempt back in July this year; it would be interesting to hear of your experience in Croatia.

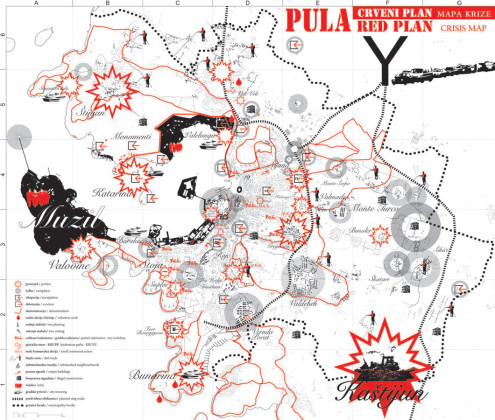

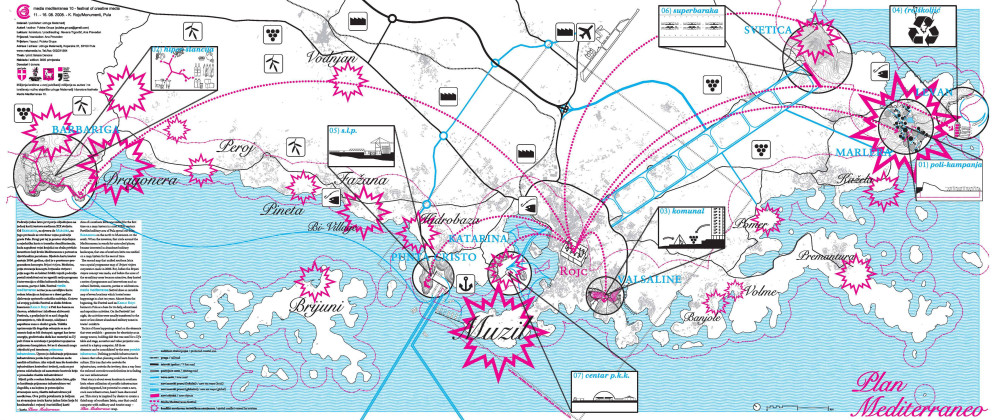

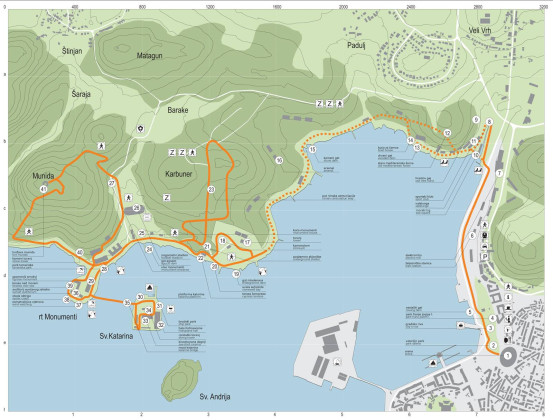

Emil Jurcan: Pula was a quite a big town, [used] as a navy base. It was formed as a modern city, and because of this army function [employed] back in the Austro-Hungaric times; and [also] after—in the Italian and the Yugoslavian regimes. And now it is a contemporary Croatian town. So basically Pula is constituted around mostly navy military infrastructure. And this industry based function was actively used until the end of the1990s, and the beginning of 2000s. During the modern Yugoslavia, the process of demilitarization started, maybe [running] parallel to the process of deindustrialization as well. Basically, while we were still students of architecture in 2005, we got involved in organizing a student workshop in one of these military areas, [which was] called Katarina. The workshop resulted in one book about the idea of the city’s capability to grasp these military areas, and how these areas—which have been gated and closed for 100 years—could be integrated into the city and the urban core. This student workshop and initiative was actually a reaction to the official plans made by the state, and [was] favored by the local authorities as well. The official plan was to exploit all the military properties, and to utilize them in a real estate market, linked with tourism. Specifically, these could be golf courts, marinas, hotels, villas, gated communities and similar projects. So our hypothesis was: This kind of mono-functionality is also a way to continue [with] the exclusiveness. These zones remain exclusive when the army and the military [offices] use them; and also when they are turned into private real estates. So citizens will be equally not welcomed in those areas.

HE: You started this as a student workshop; how did the Pulska Group develop in time? With the participation of the general public, or mostly with architects participating in the actions and designs?

EJ: In the beginning, we were supported mostly by citizens, local groups and initiatives. The idea of a workshop [directed] towards a discussion about the future of military zones was not welcomed by the political authorities, but it was also not welcomed by the architectural associations, or institutions, in that specific moment. Nevertheless, maybe for three or four years, we developed activities together with NGOs, ecological groups, citizens and so on. These ideas and projects slowly started to transform the [existent] opinion inside the architectural and urbanism discourse. So two or more years later, not only in Pula but similar activities from other Croatian cities, mostly in Zagreb, Dubrovnik, or Split, and so on, started to emerge. Well, different kinds of “right to the city” initiatives were formed; basically established against land speculation, privatization of the water coast etc. So these all together [were] in a kind of network that gradually transformed the ideas of the Croatian Architects Association, and the local architecture institutions. This resulted, for example, in 2012, in the Pulska Group’s participation to the Venice Architecture Biennale where we represented Croatia with a project that focused on the demilitarization of the Pula area.

HE: What happened to these military areas in Pulska following your struggles and actions?

EJ: Basically, nothing happened. The official plans were more or less unchanged in the last 10-15 years. None of the suggestions from the public, citizens, urbanists, architecture institutions or faculties were taken seriously by the authorities. The official plan of privatization of these military places is very ambitious. We are speaking about [an area of] 300 hectares of land. Some of [these places] are buildings that are [part of] cultural heritage. Between 2008 and 2010, the economy collapsed, and there was no private interest to invest in these areas. Nevertheless the authorities are keeping these areas gated, and closed, [until] the next opportunity. They hope the real estate market will recuperate itself. The position remains the same for years; the only thing that actually happened was that in these 10-15 years, the buildings in the area have been degrading. One of these buildings could have easily been utilized 10 years ago when there was a discussion about where to put a student campus, a university or a similar program which was needed in town. These kinds of programs could have been easily adapted 10 years ago in the existing buildings—now this is getting quite impossible without big investments.

HE: Pulska Group evolved into Praksa, an engineering cooperative for design, urbanism and architecture. What was the reason behind this change? What are the differences between the Pulska Group & Praksa?

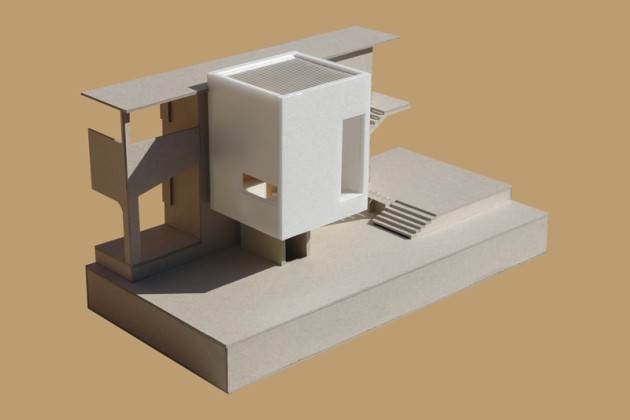

EJ: So in the beginning, Praksa Cooperative was treated only as a formal continuation of the Pulska Group activity. Pulska Group consisted of architects from Pula, about five to nine people. And at one point in 2011, we decided to register a cooperative that can gather together architects who were working independently. [We decided that] this should work as a horizontal network, not as a company which has a business hierarchy. Different architects, different members of the cooperative could perform their activity, profession and work independently, or in equal positions with other colleagues. Very soon, however, we realized that the focus of Praksa is quite different from focus of the Pulska Group. The focus of Praksa is architectural production in a plastic sense of designing space, working on architectural projects; while the Pulska Group had a social or political focus and different internal dynamics. Because the projects of the Pulska Group were not actually means of architecture, but [were instead] means of addressing general social or political problems, and the work of the architect was employed in [accordance with] that discourse. So it enabled the collective to work more like a homogeneous body without an outer shape, present for the public, as a wide group, and as a part of a larger movement. We soon realized that this was not possible through work which was focused on architectural production. So Praksa developed in a more autonomous direction. Now Praksa is still mostly an architectural network of offices. We have different members, who have their own individual practices, but who are together in a network and are related with each other. Also we tried to use this cooperative as a social center in Pula. So in a sense, we have our studios, and space for an office, which are financed by the architectural activity and different social, political and artistic groups, and movements in the town get together here, and we have a kind of autonomous production. We use the architecture business in a way to finance the independent, artistic and political activity, in order not to be only dependent on public funds.

HE: On your Praksa website, we see a list of tools that the collective has. What is the importance of sharing among the members of the collective, and how does sharing help in building a strong community?

EJ: This is also one difference that evolved with time and experience. And it became quite a big difference between the Pulska Group and the Praksa Cooperative. Pulska Group was the name and the identity that determined a kind of social approach to urbanism and architecture. If you mention the Pulska Group in Croatia, you would get this specific approach to architecture and activism. On the other hand, we realized the Praksa as a cooperative feels that its members act independently as authors of different works. And we use Praksa cooperative only as an infrastructure that we share. We share [that] space for production and we share those tools you mentioned—all tools [including] for example; the ones to make architecture models, silkscreen printing, photo studio, etc. This is the idea that started in 2011, and the first period was to open an architectural office. So we decided to open this architectural office that would be self-managed. We have also a pragmatic interest in it—that we can spend less money if we have common infrastructure enabling us to work independently.

HE: Both of these organizations are collectives with democratic structures. How do you manage the decision-making processes?

EJ: In Pulska Group’s decision making process, with its political and social body, the topics involved are questions of tactics inside a more or less dense political struggle. So the decision making process around that [includes] meetings and assemblies. These could be assemblies of neighborhood organizations that gather 200-300 people; or an operative meeting of five people. But this kind of decision making process is not continuous; it happens when there is a long period of political struggle. When there is something we have to react to or defend, then we have these pop-up horizontal structure meetings.

Praksa cooperative is an economic institution and it has to run continuously. Its management has to be regular and on monthly basis. So, in order to exist it has to be managed. Also the topic is completely different than the Pulska Group one. It is not political. Praksa is more related to classic idea of self management and how it was employed in Socialist Yugoslavia where you had an assembly as a democratic body which was dealing with economic management while the political one remained unchanged. Inserting democracy into the economic process is basically the essence of a cooperative. The topics of division of profit, investments, labor, everything regarding economic and financial aspects of management is decided by an assembly of members. Every member has an equal responsibility and opportunity to intervene in the management of the cooperative. This is maybe the more bureaucratic part of democracy.

HE: You have a unique history, without the Soviet interruption, and so on. How do people see the idea of participation and collaborative bodies in Croatia?

EJ: First of all, I am not quite familiar to situations in other East European countries, so I can’t compare it to other ex-Eastern bloc members. But regarding Croatia and Yugoslavia in general, the process of historic revision; trying to equalize the communism with the Nazi regime… This is the general process which is happening in the whole of Europe, especially in the Eastern states that had the Communist regime before. Croatia is no exception. Public opinion about the cooperative in Croatia is quite hostile. And cooperatives are regarded as part of the past regime which is regarded to be totalitarian. So let’s say that there is quite a negative opinion towards the idea of participating, and towards having collaborative bodies. The general opinion is against this kind of organizing. Precisely because of this it is very important for us, first of all, to have an egalitarian and democratic body inside the economic domain at the core of capitalism. And secondly, to have an institution which is openly political inside this economic domain. So we are not trying to camouflage our leftist ideas. We are explicit as a cooperative as production has a political position in the current society. We find it important to make this kind of statement in a business or economic domain. Economy and business are not neutral and independent from the political domain. In contrast, if we are living and working in a capitalist society, it means that economy is exactly the place where political issues should be addressed. This is something quite important for me, and it was also important when we were making the cooperative.

HE: In discussions around public spaces, the public is mostly ill-defined in conventional urban management. In some cases the public’s participation is not considered necessary, while in others, public attention is really hard to draw. Have you found or discovered any formulas to overcome these issues? How do you generate the public existence in your activities?

EJ: Well I have a very dubious opinion regarding the public participation process, which is partly based on a personal experience in Pula, and partly based on a hypothesis. Public participation regarding public space issues has two problems for me: first of all, public space is managed by existing institutions and authorities in accordance with their general interest which is a liberal economic approach to space production. In my experience, the public can participate in this process only if the general interest remains the same—you can’t participate in a way [that] you can change it. You can only discuss about the methods, the modes and the levels through which the general interest will be applied. I don’t see a lot of sense in this kind of participation. When the participatory process in urban planning of Pula went in a direction that would abolish this general interest, then suddenly participation process was turned into a political struggle. And I think this is happening continuously if things are kept inside this frame of liberal policy, of managing public space with economic methods. If something remains inside this frame, then the public can participate. If it wants to go beyond this frame, then we are not speaking about special issues anymore, we are speaking about some structural changes in the society. And then the story about space design and architecture becomes quite irrelevant. The other problem with public participation is rooted in an idea we have about architecture as form-making process. On the one side architecture is applied art, which means it applies its form to the existing society. But on the other side architecture is the most durable and long-lasting art which means it survives any society that produced it. So architecture has to be applied to the existing society but with the clear idea about the future of that same society.

Exactly because of this ambiguous position of architecture I think we should really discuss a lot about the question: In which sense is the architecture’s form-making process autonomous critical? Because it has to be autonomous in a way from the existing society if it wants to overpass it; and on the other way, it has to be applied to the same society but with the clear idea of translating it into desirable future. According to my experience, public participation, similar to democracy, has one structural problem: It makes shift from a radical standpoint toward a consensus, a status quo. In an architectural form which is produced through public participation process, it is very difficult—maybe even impossible—to reach a radical expression, a radical definition of space, which then consequently disables radical ideas of future.

HE: What is the limit to illegality in your actions? How do you embrace the conception of civil disobedience in your collective works in relation with the skeptical view on participation?

EJ: This was the topic of a series of lectures that I did in the previous year, which was called “The Subversion of Form in Architecture.” Is it possible to be critical, even to be subversive, by producing an architectural form? This is a question that I find quite difficult, but also quite necessary to address. The question of illegality in architecture is quite simple. Every aspect of architecture has to be formally approved by the authority itself with a building permission, etc. which in the context of Croatia means year or two of different approvals. This disables architecture to be explicitly anti-authoritarian, because it is embraced by the authority. It can’t be produced without the authority. So the illegality in architecture doesn’t exist. Aldo Rossi said there are no buildings in opposition, they are all positional ones. Nevertheless, we have our opinion about the society we live and work in. We can express our critical opinion in the work we are doing. And this is my interest: how to express a critical position towards the current situation and how to express this critical position inside the legal form of architecture. This is something I find very difficult but quite necessary to address.

HE: Lately, we started to hear criticism on the inefficiencies of the folk political implications, the local and the immediate reactions of people to certain issues which are considered as non-impact. What is your opinion on that? How can a public action be successful; and what can be the tools to achieve this?

EJ: This is a very difficult question to answer without being defeatist. When we look at your experience in Turkey, or experiences in EU or USA etc., generally, we see that the political struggle is getting radicalized. I see two aspects [of it] which are quite antagonistic. One is the civil society with its internal network, institutions and structure, which is managing everyday life. The other one is the political activity which has its goals and ideology that is beyond this society. It’s the classical Hegelian division. There are political issues and civil issues—the two aspects of everyday life. And my opinion is that the more things get radical in the political domain, the less space of maneuver the civil network and society have. The Pula experience was that of a civil movement struggling against the privatization of the military areas, [trying] to keep them public. The movement occurred in 2009-2010 when political issues were quite in the background; and society could perform activities or demand a change in the planning procedures. But as the political positions became more radical and ideological we had less and less space to appear in a public domain and consequently we had less opportunity to initiate a negotiation process.

And I think it has been happening for last five years. We are witnessing a disappearance of space of negotiation and the civil networks that form a society are consequently getting more narrowed. This is definitely not something where we can see any kind of a success or impact of a civil movement. So in general, I think the problems are getting more and more abstract. And we are not fighting for one park or one part of the city, or military zones; we are fighting for the concept of society in the most abstract level.

Related Content:

-

Knowledge Transfer By Co-design

Hulya Ertas in conversation with Cristi Borcan of studioBASAR on the potentials of urban commons and co-design processes with communities in the specific context of Bucharest.

-

Energy Self-Sufficiency for Public Activation

-

Urban Development through the Culture of Volunteering

Bilgen Coşkun and Dilek Öztürk talked with sociologist and Living Cities member Jennie Björstad, about social inclusion, “yes culture” and the role volunteers for urban development.

-

Participatory Dialogues for Urban Design

Bilgen Coşkun and Dilek Öztürk talked with architects and urban planners Christelle Lahoud, Pontus Westerberg and Klas Groth from UN-Habitat about designing smart cities through participatory planning approaches.

-

Participatory Design is the New Black

Cities are complex organisms that are able to develop themselves at an incredible speed and in different conditions.

-

Collaborative Work Through Community Building and the Other Way Around

The fourth edition of Glocal Camp was held in Gran Canaria and Tenerife between 4-16 April. And here is an insider review

-

Urban Laboratory

-

Green Extension

01.02.2017

01.02.2017